The Wellcome Library collections include the historical Medical Officer of Health reports. These reports have long been a valuable resource for social and medical historians researching 19th- and 20th- century public health in Britain.

In 2013, as part of the Wellcome Library’s mass digitization program, the reports for the Greater London area went online as London’s Pulse: Medical Officer of Health reports 1848–1972, a freely available website with more than 5,500 reports (wellcomelibrary.org/moh). Any gaps in the Wellcome Library holdings were filled by reports digitized from the London Metropolitan Archives collections, so the final set of reports is very close to a complete set of all the existing reports for London spanning 124 years. The project was co-funded by the Wellcome Library and JISC.

In the 19th century, the Medical Officer of Health (MOH) represented a new kind of health official, one who took a more scientific and systematic approach to monitoring public health. As well as recording statistics for births, deaths, and diseases, the officers’ work expanded throughout the next 100 years to include the inspection of the following:

- Schools

- Housing and sanitation

- Working conditions

- Food

- Social services such as child and elderly welfare

All their findings were recorded in the MOH report. Published annually by local authorities, the reports provided regular “snapshots” of health, social, and working conditions at a local level.

There was no fixed format for how the data was presented; each MOH had his own method and style. Medical officers also had a great deal of autonomy over the content—many pursued their own personal research interests (for example, the 1909 report for Willesden includes an anthropological study of European face shapes (wellcomelibrary.org/moh/report/b1979664x/138#?asi=0&ai=138&z=-0. 3306%2C-0.0156%2C1.6535%2C0.7474), as well as reporting on local issues.

This highlights a problem with the reports: They are hugely variable in content and format. Many of the earlier reports lack indexes and lists of content. The reports are a mix of written analysis, tables of numerical data, and graphical displays of statistics.

LONDON’S PULSE PROJECT

The MOH reports are a familiar sight to Wellcome Library staff. Users researching public health and social history in England and Wales frequently request them. It’s not unusual to see researchers in the library with a trolley-load of reports laboriously going through each report to find relevant bits of information. Frequent use has led to inevitable deterioration, which made the reports a prime candidate for digitization.

The Wellcome Library is in the midst of a large-scale digitization program. We had already launched one major digitized resource, Codebreakers: Makers of Modern Genetics (wellcomelibrary.org/collections/digital-collections/makers-of-modern-genetics), based on 22 archive collections held by the Wellcome Library and five library partners. Digitization is becoming part of “business as usual” for the Wellcome Library (and many other libraries and archives). Building on what we learned from Codebreakers, we wanted to experiment with more innovative, accessible, and sustainable models for presenting digitized content.

The variety of special content and identifiable users made the MOH reports a perfect choice for a pilot project to explore and develop new search and access models while utilizing our existing resources, such as the library catalogue and our in-house media player.

DIVERSE AUDIENCES

The first stage of the project was to consider our users and determine their needs.

We identified several potential audiences for the digitized material:

- Existing academic historians

- An “amateur” audience interested in local studies or family history in London

- Researchers working with text and data mining techniques

We interviewed a range of these users to find out what they thought about digitizing the London reports. Here’s what they told us:

- They liked the idea of digitization but wanted more than images of the original documents.

- They wanted the ability to copy and paste sections, as well as download whole documents.

- They wanted to search across all reports as well as browse individually.

DESIGNING THE SITE

With the information from users in mind, we moved on to the next phase of the project. All the reports were both photographed and OCR-converted to enable full-text searching and downloading in several formats. We were particularly keen to enable researchers to make maximum use of the large quantities of data in the reports, so 275,000 data tables were extracted from the reports and converted to text, XML, and CSV files for download.

Above all, we wanted to give users control of the content. In design terms, this meant providing flexibility of search, display, and download. In addition to individual download options, a section about using the report data (wellcomelibrary.org/moh/about-the-reports/using-the-report-data) provides access to the whole corpus in several formats for download, so that users can do large-scale data mining, create data visualizations, or even build their own interface—the ultimate in content flexibility!

Apart from user needs, we had several requirements of our own. As far as possible, we wanted to use the existing metadata from our library catalogue as a basis for search, rather than indexing from scratch. We had already developed a media player to display digitized content of all types, from artworks to video, and the project allowed us to enhance the player and test its functionality. The site also had to operate in the context of the larger, mobile-friendly library website (wellcomelibrary.org).

The specialized nature of the content meant that some sections of our target audience would be unfamiliar with the reports and their potential value for nonmedical topics. To help with this, we commissioned Rebecca Taylor, a history professor at Birkbeck, University of London, to write several short articles on different aspects of the reports (wellcomelibrary.org/moh/about-the-reports). We also built an interactive timeline (wellcomelibrary.org/moh/timeline) for the period covered by the reports because the reports were so closely related to changing legislation and events such as the creation of the NHS (National Health Service). The articles and timeline are second-level pages on the site and accessible through site navigation.

We intended both these measures to provide mediated access for both new users and those requiring some initial support in their research. More confident and experienced users could go straight to the search interface, prominently placed on the London’s Pulse “homepage.”

SEARCH OPTIONS

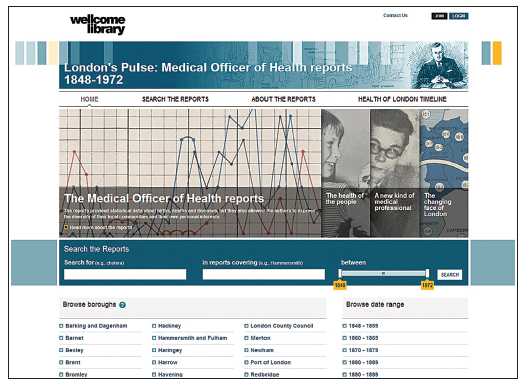

Search options on the site provide maximum flexibility, designed to suit a range of different search needs. (See Figure 1 below.)

Figure 1: Search options on London’s Pulse provide maximum flexibility.

The structured search interface consists of the following:

A free text search box

A location search box with controlled vocabulary and a drop-down list of suggested options

A slider to set the date range

These can be used individually or in combination. Users can search for any combination of topic, place, and date across all the reports. As well as the search interface, the homepage provides the option of browsing the content by date range or modern London borough.

Such an apparently complex combination of search tools not only meets different user needs, but it also allows for the variation in content and format among the reports. During the past 150 years, the social and political organization of London have changed several times, so the same geographic area might have several names or fall under several different authorities.

A researcher wanting information about a particular area can, with the benefit of the location tool, enter a place name and be offered a choice of different names that correspond to this area of London at different time periods. The controlled vocabulary also prevents users from searching for names that don’t occur as locations in the titles of reports. Similarly, browsing a current borough name pulls up any variations in names and accounts for boundary changes.

Lalita Kaplish is assistant web editor, Wellcome Library.