|

| These (below) are the two icons that our staff members created. We ultimately went with the one on the bottom so people wouldn’t get the idea that this tool searched only books. |

|

|

Arizona State University (ASU) is a large research university located on four campuses in the metropolitan Phoenix area. It serves approximately 65,000 students as well as an ever-growing online-education population. Even though I work in a large library that serves a large university, it was not a given that we would purchase a web discovery tool for our collection. We did so in order to meet the needs of our users.

Students Expressed a Need

Many of our subject librarians, web librarians, outreach librarians, and administrators had heard repeatedly from students that they wanted and needed an easier way to access electronic library resources. In addition, members of the university’s administration recognized the value of library resources and services for the success of students and faculty, and they requested a way to easily integrate them into university systems. At that time, in summer 2009, we had no way of meeting that need in a systematic manner. With no solution offered by the library, the university technology office had integrated several databases into a search box on the student and faculty portal (called MyASU). The tech people selected databases according to which ones would be easily integrated into their system. Needless to say, this is not the way a librarian would select resources! This pressing need motivated the ASU Libraries’ staff to evaluate emerging products and to select one that would best meet both our public interface needs and our staffs’ back-end workflow requirements. The system we selected was the Summon web-scale discovery service from Serials Solutions (www.serialssolutions.com/summon).

Once we’d chosen the system, the project manager set up timelines and milestones for every aspect of the implementation. A key strategy of this was including marketing and promotion planning from the start, rather than waiting until the system was almost implemented before planning the “advertising.” As a result, we took a holistic approach to the whole process, thinking of our users’ needs and seeking their feedback throughout the process. We planned several distinct stages that built upon each other: naming the service, developing visual identity components, integrating the tool into as many university systems as possible, and developing and delivering promotional messaging. Throughout the entire process, we kept in mind the basic motivation for purchasing and implementing this resource: We wanted to reduce barriers between users and resources. This goal underlined many decisions along the way.

What’s in a Name?

One of the earliest decisions we made was to name our local implementation of Summon. Summon was a brand-new product, even to librarians, and its name would not have meaning to our users. We decided we wanted to develop our own identity, one that we could tie in with our library and university, and we started with the name.

In developing the name, the Summon implementation team (I was a member of the team’s promotion subgroup) brainstormed many different options and argued rather passionately for various options in online polling. Two categories of names emerged during this process: names that were explanatory and tried to indicate what the tool was and names that were unique, did not have meaning, and would need to be explained. The options in the “explanatory” category were Library One Search, Library Multisearch, and Library Single Search. The options in the “unique” category were Suma, Sigma, TheBox, and ASU-L. Many members of the implementation team discussed the merits of each type, but it ultimately came down to two things: our users’ feedback on the options and how the naming would match up to our goal of reducing barriers.

For many years, our web services librarian has utilized various forms of user testing and of gathering other user feedback to make informed decisions in crafting web-based interfaces for our library systems. In this case, we utilized members of the ASU Libraries’ student advisory committee to get their feedback on the potential names and, subsequently, on the logo/icon associated with it. We emailed the options to 15 students. Some of their key responses were: “Library One Search makes sense. Tells you everything you need.” and “Everything in one place. I get it.” Another response reinforced our goal of reduction of barriers: “I hate when things are hard to understand or complicated. It needs to say what it is.”

The fact is that we could have gone with a “unique” name and, with repeated messaging, educated our users so they understood what a phrase like “Suma search” meant. Libraries around the world have done so with success when naming their online catalogs. Upon reflection, we decided that was not the best option for our users. We did not want them to have to pause to think about what the tool was or what they could find in it. The goal of reducing barriers, supported by student feedback, directed us to choose an explanatory name: Library One Search.

Developing a Visual Identity

We planned to create a logo/icon for Library One Search simultaneously with the naming process. Initial plans called for a contest for graphic design students to develop the icon, but that plan was abandoned due to the very aggressive implementation timeline. Risking an unsuccessful contest, and possibly needing a Plan B, was not an option. Instead, we decided to hire a professional designer to develop the icon. As clients, we could set the terms and timeline and be specific about what we were looking for.

As some of our team members were vetting professional designers, the library’s in-house digital production staff went to work developing “placeholder” icons that would demonstrate the criteria we prioritized: The icon needed to be flexible, with components that could be used separately, and there needed to be a connection to our university’s branding components. Much to our surprise and delight, the placeholder icons were more than adequate for the job—they were perfect. Using the university’s branding elements of a specific font and color scheme instantly made our icons seem like they fit into ASU’s communication stream. Moreover, the vector-based designs were simple enough to manipulate and maneuver into a variety of graphical environments. Saving the funds earmarked for this graphic design work was a bonus and served as a reminder not to overlook the skills and talents of our staff.

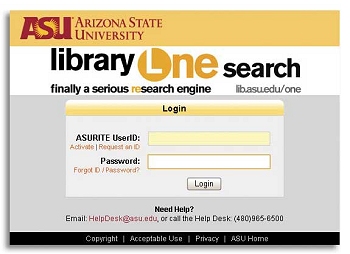

While we recognized that one of these icons was going to be the one we used, we didn’t know which it would be. We had two versions: One utilized only text and shapes, and the other incorporated the international library symbol into it. We took the decision back to the students, and this time they didn’t provide us with overwhelming feedback to choose one over the other. To make our final decision, we went back to what we thought would present the fewest barriers to the resources. We chose the one without the library symbol, as we thought it could potentially evoke only traditional library resources (books), and we did not want to risk having our users think they could find only books with Library One Search.

Integrating Into University Systems

It was very important to us to find ways to integrate Library One Search into as many of the library and university systems as possible. We believed that no clever advertising campaign would be as effective as placing the tool where the students and faculty are, where they could easily find it when they needed it. We also were focused on our goal of reducing barriers and were committed to not making users have to look for the search box.

We first integrated Library One Search into our own primary system, the libraries’ website. The January 2010 launch coincided with a planned update of the main library webpage. The web services librarian, who was also the Summon/Library One Search project manager, placed the search box front and center on the website.

Because of our partnerships with both the university’s technology office and the provost’s office, the Library One Search box was immediately integrated into the MyASU student/faculty portal. The previously developed search box that had provided access to a few select databases was replaced with the Library One Search box (complete with the distinguishing icon). Students who were on the portal to access courses, financial accounts, advising information, and other tasks were now able to quickly search for materials without taking an extra click (or two or three) to go to the libraries’ site.

The university’s primary course-management system, Blackboard, was another target for integration. The university technology office and the web services librarian worked together to develop a library search module for Blackboard. Faculty members can now add this module to their course sites. It provides access not only to the Library One Search box but also to resources such as the catalog, LibGuides (our librarian-produced subject and course guides), and online electronic journal title search. This integration will be new for the fall 2010 semester. We believe that having the search tools at the point of need, where students are doing their work, will be the ultimate in reducing barriers to essential library resources. We also created a Library One Search widget for subject librarians to integrate into LibGuides and the library’s browser toolbar. We will continue to look for more systems to integrate with, always with the goal of placing Library One Search where our users will want or need access to online resources.

Telling Them All About It: Designing Promotional Messaging

Throughout the implementation process, the team’s promotion group brainstormed ideas for an advertising campaign. The original ambitious plan involved “cheeky” messages, starting before the launch of the tool in order to build interest and curiosity. We had draft signage created and showed it to a group of university faculty members and administrators for feedback. The group appreciated our attempt at a lighthearted tone targeting students but advised caution both in terms of messaging and timing. There were a couple of ideas that they thought needed to be vetted by general counsel, so they were immediately discarded. In addition, they didn’t think we should pre-advertise the service and advised waiting until we were sure that the implementation would be a success. They emphasized that we were only going to have one chance to make a first impression, and we should make that count.

Ultimately, we abandoned the truly cheeky slogans and settled on one of our core ideas: This was a search-engine-like tool, but it was for serious research. With the faculty’s approval, we decided to emphasize the research element and settled on two slogans that we’d use repeatedly: “Finally a serious research engine” and “Researching has never been this easy.”

Again, we were able to capitalize on our relationships with the university technology office and the provost’s office and were able to place ads into major university systems. Again, we targeted the MyASU student/faculty portal. Even more significantly, we placed ads on the universitywide web authentication screens where students, faculty members, or staffers sign into any system. These had a big impact, as we learned when we questioned students a month after launch. Asked if they knew about Library One Search, their responses could be summed up as, “Of course, you can’t miss it—it’s there whenever you log into anything.”

Within the libraries, we utilized both digital signage and vinyl banners. The vinyl banners are 9' tall and are placed in the lobbies of four of our seven libraries, repeating the icons and the slogan. The banners are noteworthy because they are the only items we spent any financial resources on in the entire campaign. Everything else used internal library and university resources without any additional charges.

Post-Launch Feedback and Refinement

After Library One Search officially launched, we gathered feedback. Students’ responses included an excited “I LOVE IT” and “I really enjoy the new layout of the search. It is user friendly and easy to understand!” Some faculty members were enthusiastic, while others observed that their “search results are often large and cumbersome.” Many of our users provided feedback on problems not with the search system itself but with difficulties with our link resolver and challenges navigating publishers’ websites. As troubling as that feedback is, it actually reinforces the strength of this type of discovery tool—the users are not struggling with the search; they are struggling with end results.

A repeated comment from a variety of users sparked one major change in how the Library One Search box is presented on our website. Users told us that while they appreciated the Library One Search box, they missed having the online catalog search on the front page. They made it clear that when they had a known item, going through the Library One Search was not optimal, and there were too many clicks to get to the catalog. The web services librarian used this feedback, as well as input from librarians, to craft a new tabbed box that provides quick access to not only Library One Search and the catalog but also to the journal title look-up and LibGuides. This new feature makes optimal use of the page while still reducing barriers to vital resources.

Students Weren’t the Only Learners

There are many lessons to learn from our experience with this project. One is to look for ways to integrate messaging into your own institution’s systems, and if you don’t have relationships with the entities responsible for them, try to build them. Also, use all available internal resources; there may be staffers with untapped talents, skills, and abilities that can be utilized to decrease costs. But most importantly, remember what your goals are and what your overall message is to your users. For us, in all our decisions, we want to convey that our library cares about our users, that we listen to their feedback, and that we acquire and adapt our systems to meet their needs.

|