DATABASE REVIEW

The BUDDIE Celebrates Black History Month

by Mick O'Leary

The 2023 BUDDIE Winner

SYNOPSIS

SlaveVoyages (slavevoyages.org) is a suite of databases that thoroughly and meticulously document thousands of trans-Atlantic and intra-American slave ship voyages over 350 years of the Atlantic slave trade. |

It is my first column of 2023 and thus time to hand out the BUDDIE, the annual Database Review Award for Best Unknown Database. This issue of Information Today coincides with Black History Month, an appropriate match because the BUDDIE winner is profoundly important for the history of people of African descent in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The BUDDIE has three criteria:

- Its content is highly important to wide segments of the information-consuming public.

- It is well-designed and responsibly curated.

- It is unknown or, at least, less well-known, than it merits. This year’s winner, for example, is quite well-known within certain scholarly communities, but its interest and value extend far more widely.

The envelope, please! The 2023 BUDDIE winner is SlaveVoyages, an encompassing record of the forced relocation of millions of African people into slavery in the New World. This work, years in the making, meticulously catalogs thousands of trans-Atlantic and intra-American slave ship voyages over 3 1/2 centuries.

SLAVEVOYAGES IN THE MAKING SLAVEVOYAGES IN THE MAKING

Antecedent research in the Atlantic slave trade has been underway for decades. Several of the leading universities in this field coalesced their work, which led to the online release of SlaveVoyages in 2008. The database received a major overhaul from 2015 to 2018. It is managed by a consortium of its participating members, including seven U.S. and Caribbean institutions, and it is hosted by Rice University. The entire project has received significant support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

SlaveVoyages is a suite of databases. The principal one is Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, which covers trans-Atlantic voyages. A companion database, Intra-American Slave Trade, covers coastal voyages in the Americas. Others concentrate on specialized aspects of the broad subject. The site is highly intuitive, making it easy to move among its sections and use its resources effectively with a little practice. It is amply supported with methodology guides, explanatory essays, and a good help section. This support system aids in bringing this extraordinary resource, once the arcane domain of scholars, to a much wider audience.

TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade documents more than 36,000 trans-Atlantic voyages. The first was in 1514; the last was in 1866, at the culmination of decades of abolitionist activity. The slave ships embarked from across the western coast of Africa, from what is now Senegal, south to what is now Gabon. They disembarked in the Americas from Massachusetts to Argentina.

These data have been extracted from an enormous mass of commonplace records: ship manifests, port logs, commercial and government documents, etc. The immense and painstaking work of analyzing and digitizing this vast trove—with its obscurities, archaic language, and tattered pages—is a tribute to the vision and commitment of the scholarly enterprise.

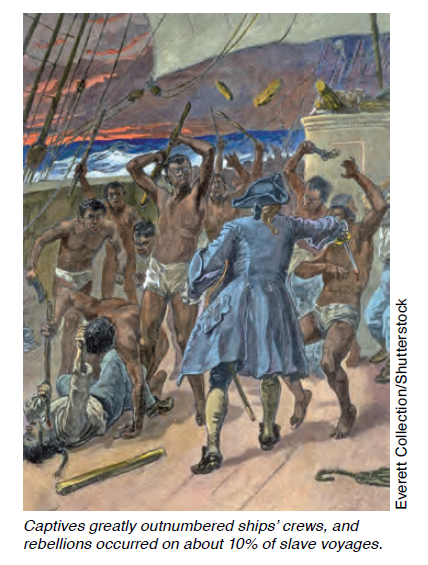

For each voyage, there is a record template that documents dozens of aspects: number and demographics of the captives, the ship’s itinerary, ship description, dates, voyage outcome, and many others. (However, most records are partially or thinly populated because of varying data availability from voyage to voyage.) [Please note that “captives” is the term used by SlaveVoyages. —Ed.] These small details can be woven into important and revealing strands. One indicator for voyage outcome is “African Resistance,” which documents hundreds of revolts. Taken together, these tell a compelling story of the captives’ continuing and resolute resistance to their sudden enslavement.

EXPLORING THE SLAVE TRADE

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database has multiple browsing, searching, and filtering tools. Table and graph tools can create custom datasets. Interactive timeline and map apps provide informative visualizations. One of these—Timelapse—is compelling. It’s an animation that uses moving colored dots, coded for country of origin and ship size, to show the actual path of each individual voyage. The thick streams of dots south of the equator clearly depict an aspect of the slave trade that Americans may not know: that a very large majority of African captives actually disembarked in the Caribbean and Brazil, rather than in North America.

Two summary tables represent the astonishing scope of the Atlantic slave trade (about which estimates vary). The database itself documents approximately 10.5 million captives overall. However, it acknowledges that this total is incomplete because it doesn’t claim to have documented every single voyage. Instead, it provides an estimated table indicating that approximately 12.5 million African people were captured and enslaved.

Other interpretative sections include a set of concise essays on the political and economic background of the slave trade and additional graphics. Two 3D videos depict the slave ship structure and transit experience, representing the horrific conditions of the Middle Passage in detail.

INTRA-AMERICAN SLAVE TRADE

Slave voyages were not confined to trans-Atlantic crossings. Once in the Americas, the enslaved were shipped between many New World locations, which are documented in Intra-American Slave Trade. (Note that these are marine voyages among coastal ports. Overland and internal waterway transports are not included.)

The database has the same structure and search/browse tools of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database. It’s a much smaller database, recording approximately 620,000 captives and 27,000 voyages. It lacks several of the interpretative tools found in the trans-Atlantic database.

FURTHER SLAVE TRADE RESEARCH

The SlaveVoyages suite has two other databases that delve more deeply into aspects of the broad theme, using datasets that complement those in the trans-Atlantic and intra-American databases:

- The African Names Database—In 1807, the U.S. Congress passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, which made U.S. participation in the trans-Atlantic slave trade illegal. Over the next 60 years, more than 2,000 slave ships were intercepted, and the names, including African names, of nearly 100,000 African people were documented. This dataset serves as the basis for the African Names Database. The names are linked to corresponding records in the trans-Atlantic database and to those in the African Origins database at Emory University, which has additional information on names and languages.

- Oceans of Kinfolk—The 1807 act also required coastal slave transport ships to create manifests of any enslaved people onboard. These records provide descriptive data on more than 63,000 enslaved people, as well as the ship and its itinerary.

THE ENDURING LEGACY OF SLAVEVOYAGES

The enforced diaspora of 12 million African people is a foundational event, not just for people of African descent in the U.S., but for U.S. and even world history. And although the slave trade stopped 200 years ago, its effects endure. They are seen in the present geographical distributions of enslaved people’s descendants. More subtle, and far more troubling, are deep patterns of social and economic subordination that continue to this day.

Resistance to the truths of SlaveVoyages also continues. A current example is the backlash against the proposed teaching of critical race theory in American schools, with the attendant risk of white children being exposed to the facts about their own history. SlaveVoyages is a bulwark against this deliberate and pernicious ignorance. With the immense force of its data and its meticulous scholarship, it is an epochal BUDDIE winner.

|