FEATURE

Building Frameworks for Long-Term Digital Preservation

by Ray Uzwyshyn

| Digital preservation is one of the grand, necessary challenges of our times. |

Libraries are memory institutions and have unique roles as stewards in the preservation of our collective histories. Creating a long-term digital preservation infrastructure is a critical area of strategic development for all memory institutions. Information comes online, goes offline, and then disappears, sometimes forever. Future-proofing this knowledge is not just a 1-year management project, but it requires a long view and a framework for achieving results over time.

Frameworks for Digital Preservation

What exactly are long-term digital preservation frameworks? What models and best practices have libraries developed to meet the digital preservation challenge? This article defines and then focuses on the best practice framework for digital preservation currently implemented at Texas State University’s libraries through its digital preservation working group. We

advocate for a structured approach.

What Is Long-Term Digital Preservation Storage?

University libraries, special collections units, and archives increasingly collect and gather information in both analog and digital formats. Well-known analog formats include books, paper-based archives, videotapes, and LPs. Digital formats include PC files, digital video media, data, and, increasingly, websites and email. Much of this information could benefit from digitization if it is in an analog format and longer-term digital storage and retrieval if it is already digital. Digital preservation storage for libraries is a very long-term consideration that goes way beyond standard IT department disaster recovery and regular records-retention mandates. It is a commitment to a larger and longer program that involves both human resources and budgetary allocations going forward. Complex ISO standards define needs for the audit and certification of trusted digital repositories and open archival digital information storage systems (ISO numbers 16363, 16919, 14721; see the Resources section for more information). Currently, there are only more than a handful of trusted repositories that completely meet these high benchmarking systems requirements.

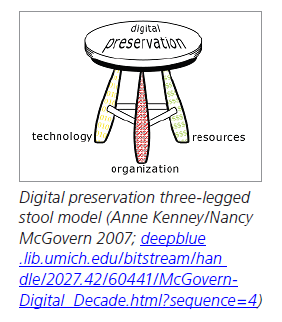

Three-Legged Stool Digital Preservation Model Three-Legged Stool Digital Preservation Model

Pragmatically, most libraries that are pursuing digital preservation follow a three-legged stool model, originally suggested by Anne Kenney and Nancy McGovern in 2007. A solid foundation for digital preservation is built on a three-legged stool consisting of organization, technology, and

resources. “Organization” leverages the respective institution’s existing human resources to build on its archival/stewardship expertise for the digital age. “Technology” synthesizes current technological capabilities with traditional library archival/collection preservation models. “Resources” uses library human resources and wider network resources, such as IT departments or national alliances and consortia.

The Unique Characteristics of Long-Term Digital Preservation

A unique characteristic of long-term digital preservation is the migration and preservation of digital file formats for long-term storage. This means that a Windows 3, Word 2 file from 1991 can be read as easily as an Office 365 Word file from 2021. This ability to make media readable is called normalization—migrating file formats forward to be read normally within present-day standard technological formats. The work of preservation and normalization is an ongoing process, continually moving file formats forward to present readability standards.

Risk mitigation for data or content is another unique characteristic of long-term digital preservation. Pragmatically, risk mitigation means creating multiple bit-level copies of a file to double-check for bit-level accuracy (called checksums) and then storing these files in disparate locations geographically, administratively, and technologically.

Consider the Chronopolis network (library.ucsd.edu/chronopolis/index.html). Originally funded by the Library of Congress, it is a geographically distributed preservation network with data storage facilities operated by the University of California–San Diego (UC–SD), Texas Digital Library along with the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TDL and TACC), and the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computing Studies (UMIACS).

Building a Long-Term Digital Preservation Working Group

For institutions that are thinking about long-term preservation infrastructures, it is best to begin by forming a digital preservation working group. This group should consist of members of the library and IT departments’ digital and web services operations—including the digitization lab, institutional repositories, core IT, and the university library archives’ special and general collections—e.g., archivists, collection development librarians, and administrators.

The group should begin by investigating and authoring a local digital preservation policy document. This document will clarify and give an overview of an institution’s digital policy framework (purposes, objectives, roles, and responsibilities), outline general procedures (digital preservation strategies and technological infrastructure), and provide a detailed plan, strategy, and timeline for implementing and publicizing the framework. Fulfilling the tasks of outlining policies and agreeing to benchmark minimums for preservation masters will also establish common ground for later, more contentious group discussions. A model for such a plan is Texas State University’s Digital and Preservation Policy Document (thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu/research/visit/policies/dig-pres-policy.html).

Digital Preservation Tools

Next on any agenda for a digital preservation working group will be an environmental scan of the current landscape of digital preservation tools to decide on the right tools. In its own scan, Texas State University’s working group decided on the open source tool Archivematica, which is middleware software for ensuring file integrity and digital preservation metadata (Uzwyshyn 2020).

Archivematica bundles microservices for normalizing files, managing metadata, and verifying file types for bit-level integrity (i.e., checksum). We first deployed production-level instances on Archivematica’s Red Hat, which is a widely used open source Linux platform. After implementation, archives and special collections staffers may begin experimenting to gain expertise in this middleware’s workflow process to create archival information packages (AIPs) that store, archive, and retrieve files and metadata for later use.

Developing a Digital Storage Needs Estimate

At the same time it is creating the aforementioned digital preservation policy documents and developing software expertise, a digital preservation working group will also need to conduct an initial storage needs estimate. This estimate will help decide what current permanent digital storage is needed, as well as the yearly additions assessed through current digital preservation work per year. It is good to develop this estimate early on to give to university IT and library administration. It will involve cost estimates for data storage and ongoing effects for the annual operating budget. It is also beneficial to give a high-level breakdown of current storage/space requirements by areas (i.e., archives, special and general collections). An example is provided in the chart on page 8.

Digital Preservation Storage Solution Recommendation

With preliminary foundations and general needs established, it is now up to the digital preservation working group to review the current landscape of storage solutions and forward a recommendation to library administrators and IT. This involves conducting an environmental scan to identify library digital preservation storage solutions and create a cost-benefit analysis. Cost per terabyte or petabyte per year will be particularly crucial factors, as any solution technically entails digital preservation storage and retrieval in perpetuity, and this will be an ongoing cost. It will also be beneficial to begin looking at both in-house solutions and comparing those to cloud possibilities (Amazon Web Services, Azure, Chronopolis, DuraCloud, etc.). It is also not a bad idea for the preservation group to look to a peer group of libraries or other memory institutions that are pursuing digital preservation for national best practices and current trends. From here, the group may narrow its focus to pragmatic options, taking in different variables to suit the specific library or institution’s needs. At this stage, it should review its progress—in creating policy, specifying software, and developing expertise—and provide a recommendation to the administrators who will review the proposal for the future budgetary funding allocations required for this infrastructure.

Our group’s process led to a recommendation for Chronopolis via DuraCloud through the Texas Digital Library. (A detailed presentation of this decision-making process is available in the Resources section; Uzwyshyn 2020.) Following the previously outlined steps will lead to a good initial foundation for any digital preservation framework.

Final Thoughts

Researchers, university faculty members, students, and donors expect a new level of service in our networked age. Digital preservation is one of the grand, necessary challenges of our times. These new processes will bring relevance and a raison d’etre to any memory institution’s existence in the digital era. By placing our libraries into this arena, we also reconnect them to longer threads of past historical legacies and lineages. In this way, we may link our present to the institutions that have defined our past through their own long-term preservation decisions. And in the process, we will define our mutual future.

Currently, in the West, we are already 40 years into the era of digital preservation. This era began in the early ’80s with the introduction of the desktop computer as a way of working. The multitude of files and important historical digital information produced since then now needs to be preserved. A wide spectrum of media formats is obsolescent or rapidly aging. These needs also continue into our present webcentric world with the web and cloud’s long-term digital preservation needs. It is important for libraries and memory institutions to begin wading into these waters. Information is disappearing daily. Significant histories are being lost for our collective future. It is also important to remember that Rome was not built in a day, and a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. We are in a digital renaissance or Gutenberg II-like period. Historical digital information artifacts are at a stage akin to that of the early incunabula in the first 50 years after earlier communication model paradigm shifts. Long-term digital preservation is needed now as these early digital artifacts begin to disappear.

|

TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY’S DIGITAL PRESERVATION GROUP DIGITAL STORAGE NEEDS ESTIMATE

Conclusions: 10–12TB/year recurring and 60–70TB permanent digital storage needed

UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES:

Thesis and dissertations project: 500GB per year

Yearbook/football negatives: 235GB per year

San Marcos Daily Record negatives 1,500GB per year

Historical audio digitization: 500GB per year

Miscellaneous imaging: 500GB per year

WITTLIFF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS:

Austin Film Festival: 1.5TB per year (2-plus years)

Lonesome Dove Digital Video Miniseries Dailies (20TB), Jerry Jeff Walker 2# audio master reel tapes

Audio digitization (Selena): 200GB per year Powers (10TB), Broyles (300GB)

O’Connor Collection/New Major Donation example (2TB)

Major Author Archives: 2TB per year, Cormac McCarthy, Sandra Cisneros

GENERAL COLLECTIONS:

Streaming media archive: 2TB per year, general collections digital serial backfiles (storage space needed, but not covered by LOCKSS, PORTICO, or HathiTrust memberships)

|