FROM THE INNOVATION LAB

Designing a Robotic Personality: A Conversation With Kyle Camuti

by Chad Mairn

| Kyle Camuti has built a system that challenges our assumptions about desktop assistants, and his work exemplifies the kind of interdisciplinary curiosity that library makerspaces should foster. |

This column spotlights emerging technologies shaping libraries, but the real secret is the people who choose to learn out loud. The Innovation Lab is a technology playground where people with similar interests in STEM meet, socialize, and collaborate while sharing ideas and learning new skills. In this issue, I'm proud to share a success story from my former student and friend, Kyle Camuti, who worked on a few projects, including his desktop companion robot, Ambit. Designed from scratch using off-the-shelf components, Ambit blends facial recognition, generative language models, and a sarcastic wit. In this interview, we discuss the build process, Kyle’s engineering decisions, and what it means to create intelligent systems that act, well, human. [This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and style. —Ed.]

Chad: What sparked the idea for Ambit?

Kyle: When I first walked into the Innovation Lab at St. Petersburg College, I had no clue what I was doing. It was my first time in college, and I didn’t know the first thing about computer science, engineering, or robotics. But I’ve always been fascinated by technology, especially with the recent boom in AI. Large language models (LLMs) and other tools were advancing so fast, and while a lot of people were just watching it happen, I wanted to dive in and do something with it. I’ve never been the type to learn from textbooks alone. I learn best by building, testing, and sometimes breaking things. The Innovation Lab became my sandbox, and I made it my mission to prove to myself that I could not only understand these new technologies but also create something meaningful with them.

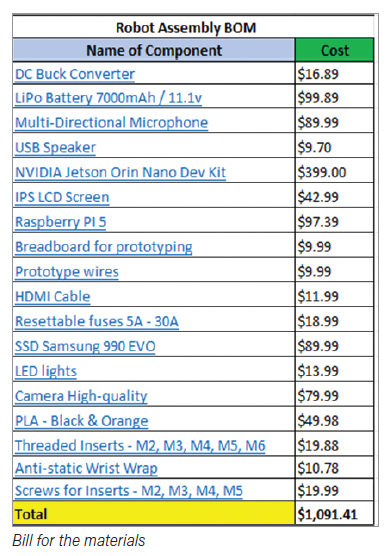

Chad: That’s great! This learn-by-breaking mindset is maker culture at its best. As you know, it is fun to prompt various AI systems to generate content, but it is a more powerful learning experience when you work behind the scenes to see how this technology really works. OK, you chose parts such as a Jetson Orin Nano, Raspberry Pi camera, servos, and SSD—give us a lightning tour.

Kyle: Ambit went through a lot of material changes, but in the end, each part served a key function. Jetson Orin Nano acts as the brain, running facial recognition and all AI tasks. The camera handles face tracking and eye movement alignment. 3D-printed CAD [computer-assisted design] parts form the body, while servo motors control the eyes for expressive movement. The speaker handles voice output, and the LCD screen displays subtitles, images, and gestures to enhance communication. Finally, the SSD stores memory data, user profiles, and everything Ambit needs to stay responsive.

Chad: And that’s just scratching the surface. Under the hood, you’re juggling speech recognition, computer vision, GPT function calls, and text-to-speech. How do you keep that pipeline humming? Oh, and I forgot to mention the Arduino in the last question. What is that doing?

Kyle: Ambit’s software stack is a pipeline made up of open source libraries and APIs that all talk to each other in real time. It starts with facial recognition and tracking, which was built with OpenCV and DeepFace. These tools were perfect because they’re open source and run great on the Jetson Orin Nano.

When Ambit sees a face, two things happen: It begins tracking the person’s position in real time and sends that data to an Arduino that controls Ambit’s eyes with servo motors. This makes it feel as if Ambit is looking at you. The Arduino also controls built-in gestures such as blinking, side eye, eye rolls, and a scan mode in which the eyes move wildly. These animations are randomly triggered or based on context, and they’re what give Ambit its quirky personality. At the same time, DeepFace runs facial recognition by comparing the live feed to a local database of user profiles. If Ambit recognizes you, it loads your private memory profile and uses that data to personalize the interaction. If it doesn’t recognize you, it creates a new one. Each memory profile is stored locally, so none of the data is sent to the cloud.

For voice interaction, Ambit uses OpenWakeWord to listen only after it hears its name. This cuts down on resource usage and avoids constantly recording or analyzing audio. Once activated, Ambit uses OpenAI’s Whisper—through GPT-4o-Transcribe—and a semantic voice activity detection (VAD) system to transcribe what you’re saying in real time. That transcription is sent to GPT-4o through OpenAI’s API, which has been prompt-engineered to understand context, personality, and which function it can call. The LLM chooses whether to respond, run a gesture, analyze an image, update a stat, or do something else. One example: If you say, “Hey Ambit, what’s this?” and hold something up, it’ll snap a temporary photo, analyze it with OpenAI’s image model, and give a response based on both the prompt and the visual context. Once the LLM generates a reply, that text is sent to ElevenLabs using its eleven_flash_v2_5 model for text-to-speech, which is expressive and surprisingly “human.” I also use its timestamp API so that Ambit can highlight each word on the LCD screen as it’s spoken.

Chad: If that sounds like a lot of moving parts, it is! What is amazing is that Ambit boots in under 30 seconds. Can you walk me through a typical interaction?

Kyle: From the moment you walk up to Ambit, it reacts. If it knows you, it greets you by name and picks up where you left off. If it doesn’t, it introduces itself and starts building a new memory profile on-the-fly. When you say, “Hey Ambit,” the screen immediately shifts to show it’s listening with a pulsing waveform or visual cue. After you finish talking, Ambit shows that it’s thinking, then responds with a natural voice. While it speaks, a waveform is animated on the LCD in the shape of a mouth, perfectly syncing to the audio. Subtitles appear and highlight each word as it’s spoken, making it accessible and expressive. If you ask it to generate an image, analyze something visually, or do a deeper task, the screen shows a separate animation indicating it’s working in the background, but you can keep talking to Ambit while it processes. The visual indicators make everything clear, when it’s listening, thinking, speaking, or multitasking, and that feedback loop helps the interaction feel more natural.

Chad: Hardware development rarely goes perfectly. What tripped you up, and how did you troubleshoot or iterate around those bottlenecks?

Kyle: Yes, there were challenges! One of the biggest was working with the Jetson Orin Nano. It’s a powerful board, but it lacks strong community support, and the documentation can be frustratingly sparse. Just flashing the OS took me days to figure out, and the issue ended up being a low-quality USB-C cord that couldn’t handle proper data transfer. That one stumped me longer than I’d like to admit.

Chad: Oh, yes, that happened to me on a computer vision project. I struggled for hours and then realized the power supply didn’t have enough voltage to run the device. I won’t make that mistake again.

Kyle: Totally! So, I picked components that were mostly USB-based or wired directly to the Arduino or Jetson, which gave me full control and reduced a lot of guesswork. But the real challenge came with syncing everything—vision, audio, gestures, memory, UI [user interface]—without crashing or lagging. That part wasn’t solved with a tutorial or copy-paste code. It was trial-and-error, hours of debugging, and slowly learning how every piece of the system spoke to the others. That’s why Ambit was the perfect project for me. I came into the Innovation Lab with no formal background in robotics or AI. I just knew I wanted to learn by building. Ambit forced me to learn hardware, software, debugging, real-time processing, and how to make all those things feel like a personality. Every obstacle was a lesson, and by the end, I didn’t just build a robot—I proved to myself that I could figure anything out.

Chad: I have said it before, but I am so proud of the work you have done, and I know you will take this and other projects you work on to the next level. That said, what advice would you give to future students exploring AI, robotics, or other emerging technologies?

Kyle: My biggest advice is don’t wait until you feel ready. You’re never going to know everything when you start and, honestly, you don’t need to. Again, I walked into the Innovation Lab with zero experience in robotics, AI, or even basic engineering skills. I just knew I was curious and willing to try. You’re going to fail. A lot. And that’s exactly how you learn. I believe that someone who experiments and fails makes a better teacher because they know what doesn’t work and, more importantly, can demonstrate how to critically think through the problem and fix it. That’s real-life experience. Kyle: My biggest advice is don’t wait until you feel ready. You’re never going to know everything when you start and, honestly, you don’t need to. Again, I walked into the Innovation Lab with zero experience in robotics, AI, or even basic engineering skills. I just knew I was curious and willing to try. You’re going to fail. A lot. And that’s exactly how you learn. I believe that someone who experiments and fails makes a better teacher because they know what doesn’t work and, more importantly, can demonstrate how to critically think through the problem and fix it. That’s real-life experience.

But the truth is, I didn’t do any of this alone. You were the reason this was all possible. You believed in me before I believed in myself. You found the funding. You connected me to the right people. You got me into conferences to build my resume and opened doors I never would’ve found on my own. And the craziest part? Even after I moved halfway across the country, you are still supporting me. You don’t give up on your students. Also, use the resources around you. There are amazing open source tools, free AI models, and communities online that can help you build. But most importantly, build something that matters to you. It doesn’t need to be perfect or even useful by anyone else’s standards. If it excites you, if it keeps you up at night thinking about what to add next, then that’s what makes it worth doing. I’m not an expert with a massive lab or fancy degree—I’m just a student who got the right support, stayed curious, and kept building. And if I can do that, you absolutely can too.

Chad: Kyle, thank you for the kind words, and I will continue to support you as you follow your career path. I am also learning from you, and for that I am grateful.

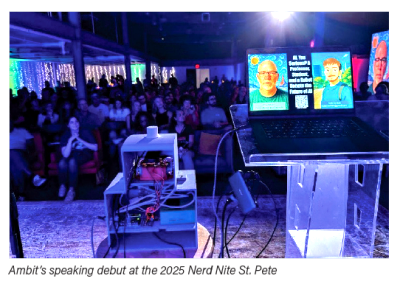

Ambit is more than a technical achievement; it is a conversation starter about the future of personalized AI and the creative potential of student innovation. In the past year or so, Ambit has undergone several iterations, spoken before an audience of more than 250 at Nerd Nite St. Pete, co-hosted a video podcast, participated in St. Petersburg College’s undergraduate research experience, and traveled to Washington, D.C., to demonstrate its capabilities at the Computers in Libraries conference. Kyle Camuti has built a system that challenges our assumptions about desktop assistants, and his work exemplifies the kind of interdisciplinary curiosity that library makerspaces should foster.

Note: The complete interview, with supplemental, interactive content, is available in NotebookLM at shorturl.at/BF4sp. |