FEATURE

From Behind the Curve to Riding the Wave: Low-Barrier AI Adoption in Libraries

by Elaine Lasda and Nathaniel Heyer

| To ride this latest wave successfully, libraries must employ both top-down and bottom-up approaches that are mutually reinforcing. |

Conversation around new technology often begins with Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations model, which describes five categories of users: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards (diffusion-research.org/research_articles/origins-of-diffusion-paradigm). When it comes to generative AI (gen AI) or agentic AI, a vanguard of innovators and early adopters has already formed within well-supported academic and public libraries. This has led to a flurry of publications and presentations. For example, at the 2025 Computers in Libraries conference, 19 of the programs and an entire track were devoted to AI presentations (computersinlibraries.infotoday.com/2025/Presentations.aspx).

This drive to dive in headfirst is understandable. Librarians and information professionals often feel pressure to justify their existence to stakeholders, a feeling amplified by technological advancements. AI is not the first technology to signal the supposed irrelevance of libraries; concerns about computerization replacing librarians were prevalent even half a century ago to form the plot of the 1957 film Desk Set. Conscious of both risks and opportunities, the profession has made integrating new technology a hallmark of its culture, causing AI to be the next significant adventure for many. But what about the rest, the so-called laggards? This term is rather unfairly pejorative, as there are practical and warranted reasons for a more measured pace of adoption.

Change-Resistant or Constrained?

Reflecting the diversity of their communities, libraries must balance a huge number of interests and needs when providing services and resources. Meanwhile, many library workers feel called to support not just the literacy, academic success, or lifelong learning of their service populations, but also initiatives to uplift the marginalized and increase accessibility, resulting in a broad and amorphous scope of work.

This wide-ranging mission is frequently hampered by significant constraints. Libraries of all types face budgetary pressures. While library budgets have recently trended upward, increases often represent a recovery from pandemic-era cuts, and recent IMLS reductions have placed libraries in jeopardy again (libraryjournal.com/story/whats-up-whats-down-bud gets-and-funding-2025). In academia, library budgets have fallen relative to other campus spending (informationmatters.org/2025/05/academic-libraries-spending-matters-for-college-student-success). Furthermore, many libraries operate with what amounts to skeleton crews, even as the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts future job growth (bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/librarians.htm). These pressures—combined with aging facilities, technological disruption, and strong political headwinds—mean that many library workers are chronically stressed and juggling too many tasks and projects, often to the detriment of their well-being and work efficiency. Thus, even those workers who are curious about AI tools may find it very difficult to carve out the time and energy to explore them.

Beyond these practical constraints, several other factors contribute to a reluctance to embrace AI. They include staff discomfort, attachment to existing processes, insufficient training, organizational inertia, and a fundamental lack of trust in AI tools (liblime.com/2025/03/17/understanding-librarian-hesitancy-toward-ai-implementation). According to the May 28, 2025, How to Increase AI Adoption in the Workplace Webinar Summary presented by Julian De Freitas and moderated by Julie Devoll, research from the business world complements this view, finding that workers often perceive AI as “opaque,” “emotionless,” “inflexible,” “autonomous,” and “not human.” While library-focused analysis tends to highlight personnel-related concerns, the business perspective focuses on the user experience of the technology itself. Both offer valid insights into the fears surrounding AI implementation.

One overlooked aspect of this hesitancy is that librarians, by profession, understand the limitations of AI better than the average person. They are primed by professional values to be skeptical of hyped-up tools that threaten user privacy and carry demonstrable risks of algorithmic bias and inaccurate outputs. This professional skepticism is compounded by additional ethical concerns, such as the environmental impact of resource-intensive AI server farms and unresolved issues of author and artist rights.

Don’t Get Caught in the Undertow

While the challenges are significant, integrating AI into library workflows and services is a task we must undertake. Our communities are relying on us to apply our unique understanding of information ethics to the complex implications and uses of AI tools. As these tools become as ubiquitous as personal computers and the internet, individual users will also need our guidance and training to employ them effectively.

Simultaneously, our profession is in dire need of the support and efficiency gains that AI can provide. Automating certain tasks can help create sustainable workloads, allowing us to focus on what is irreplaceable about libraries: the human-to-human interactions and rich and tactile experiences of resources, dialogue, and spaces that form the core of our mission. The great news is that the innovators and early adopters have already sailed ahead, leaving useful conclusions in their wake. Concurrently, our vendors are developing chat agents for curated search systems, using proprietary large language models (LLMs) to facilitate natural language searching. Engaging with vendor representatives for training is crucial to fully leverage these evolving tools.

What AI Can Do |

Example 1 Example 1

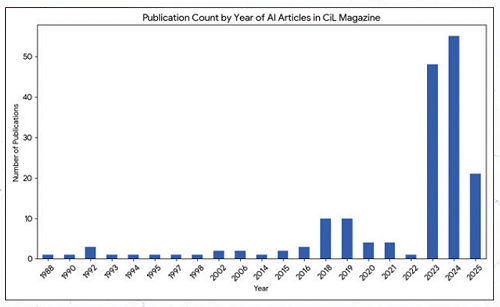

Number of AI-related articles published in

Computers in Libraries Magazine from 1988 to

2025. The chart (right) illustrates a significant increase in

the volume of publications on the topic of Artificial

Intelligence, with a dramatic surge in articles

from 2023 onwards. This trend suggests a growing

focus and interest in AI within the library and

information science community. [Google Gemini

Pro 2.5 created this chart and paragraph. The process

took two prompts and less than 3 minutes. The

data for 2025 is not for a complete year. Neither the

chart nor the paragraph has been edited at all. —Ed.]

Example 2

The authors used this AI-generated summary of key

AI authors in Computers in Libraries to determine the

approach we wanted to take with our own article. Total

time spent analyzing the data was less than 5 minutes.

[This has not been edited at all—only the bolding was

removed for clarity. —Ed.]

Themes for the Top 10 CIL Authors Writing about AI:

- Affelt, Amy: Focuses on AI, particularly agentic AI, its

implications for libraries and librarians, and the evolving

landscape of data and technology. Mentions specific

entities like Google and discusses future trends.

- Bates, Mary Ellen: Centers on librarians and their role

in the age of AI. Explores topics like search, open access

(OA), the importance of user voices, and the skills

needed for information professionals.

- Breeding, Marshall: Concentrates on AI and emerging

technologies within libraries. Discusses trends,

capabilities, discovery services, and the future of library

services.

- Dixon, Neil: Explores the intersection of AI, digital

literacy, and library services. Mentions AI generators and

their application in creating text-to-art, emphasizing

the evolving role of libraries.

- Huwe, Terence K: Focuses on data, particularly big data

and digital trends in libraries. Discusses collections and

their management over time.

- Keiser, Barbie E: Primarily discusses AI in the context of

research and tools, mentioning platforms like Clarivate,

Scopus, and publishers like Wolters Kluwer. Focuses on

the user experience with these resources.

- Mairn, Chad: Explores AI and emerging technologies in

learning and education. Discusses research, literacy, the

role of human intelligence, and the development of new

tools.

- Ojala, Marydee: Focuses on AI in search, particularly

within a business context. Mentions specific AI tools

like ChatGPT and concepts like generative AI, SWOT

analysis, and the web.

- Pichman, Brian: Focuses on technology and AI tools

within library spaces. Discusses the evolving role of

technology in libraries.

|

Learning to Surf the AI Waves

Ultimately, AI adoption presents an opportunity to eliminate some of the very busy work and address constraints that make exploring new technology so difficult. To ride this latest wave successfully, libraries must employ both top-down and bottom-up approaches that are mutually reinforcing.

For the Leaders

The breakneck pace of AI development makes long-term strategic planning uniquely challenging. Instead of creating a rigid road map destined to be out-of-date within months, leaders can use agile approaches such as scenario planning to prepare for multiple possible futures. Another effective method is to treat a strategic plan as an open-ended framework for inquiry, rather than a definitive guide to a specific application of or stance toward AI.

Until AI matures as a technology and legislation catches up to real-world conditions, certain questions should remain central to this inquiry:

- What does our service population think about AI at this time, and are we, as an organization, aligned with local consensus?

- What ethical, legal, and moral concerns are at play in the discourse about and application of AI, and what is my organization’s current position on these topics? How are we determining our position?

- What does it mean to be “human,” with the new information we have about what machines can do right now? How can we support the thriving of humans specifically, both that of our workers and our service population?

- What practical and structural approaches can we take to effectively support our users and workers in both skill-building as AI users and in adjusting to paradigm shifts in society, work, and culture brought about by the proliferation of AI?

- How will we collect, leverage, and disseminate valuable worker insights on AI tools?

- Where can we make productivity and efficiency gains in our organization right now using AI tools? How will we responsibly, effectively, and ethically channel human potential or resources unlocked by these efforts toward our mission?

In this fluid environment, strategic plans that define measurable objectives around experimentation, discourse, research, and inquiry—and that center on human beings as opposed to the tools themselves—are far more likely to be successful and productive than those that attempt to predict or direct how this technology will ultimately pan out. Any strategic plan must also tackle worker resistance, which often stems from inertia, comfort with existing processes, and the fear of obsolescence. To foster a culture of innovation, leaders can look to examples like the University of Toronto, which deployed strategies such as keeping AI as a recurring leadership topic, running a weekly staff communique on AI, and implementing small-scale, reversible projects (Gupta, V. 2025. “From Hype to Strategy: Navigating the Reality of Experimental Strategic Adoption of AI Technologies in Libraries,” Reference Services Review, Vol. 53 No. 1, pp. 1–14, doi.org/10.1108/RSR-08-2024-0042). Consider also exploring resources such as Bare Bones Project Management: What You Can’t Not Do (google.com/books/edition/Bare_Bones_Project_Management/zV6rAAAACAAJ?hl=en) and the library-specific Fostering Change: A Team-Based Guide (ala.org/sites/default/files/acrl/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/FosteringChange.pdf).

For All Library Workers

Whether you are an administrator, librarian, or paraprofessional, gen AI offers the chance to gain breathing room to focus on impactful work. Think of it as having your own personal assistant. While this assistant is new and sometimes makes mistakes, having a fallible aide is better than having none at all.

A structured approach to integrating AI into your workday is most effective. A great first step is to inventory your regular tasks. Identify which duties constitute repetitive busywork, time-intensive data analysis, or routine text drafting—all areas that are ripe for an efficiency boost from AI. For example, the authors of this article used Google Gemini to analyze metadata from a spreadsheet of articles, generating insights on key themes and authors in under 15 minutes. Once you identify potential time-savers, you can find how-to content tailored to your specific needs.

Additionally, scan your work life for tasks or projects that cause boredom or frustration, rather than inspire excitement and enthusiasm. By providing background on such a challenge, you can draw from a vast dataset of cross-industry knowledge to generate a jumping-off point for your next step, preserving your creative energy for what matters to you. Also, consider if your projects involve reinventing a wheel someone else has already built in another library or even in business and industry. For example, AI chatbots are becoming ever easier to customize, acting as a hivemind that can rapidly research and adapt existing ideas for your circumstances or population.

Once you’ve defined a plan for how you will use AI tools, there are numerous low-barrier opportunities to get your feet wet. One concern about AI is to exercise caution, because many open source LLMs such as ChatGPT and Google Gemini use your prompts and inputs to train their models (wired.com/story/how-to-stop-your-data-from-being-used-to-train-ai). While ChatGPT has strong name recognition, look for tools that offer Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to mitigate the risk of hallucinations or fabricated outputs and those that partition your inputs from being vacuumed up into the LLM (cloud.google.com/use-cases/retrieval-augmented-generation). A great article by Lorena Santos goes through an extensive list of tools and their uses (medium.com/@lorenamelo.engr/a-guide-to-public-large-language-models-you-can-use-today-fadc23a29f0e).

Skilling Up Is Necessary—and Inevitable

As you engage with these tools, you will develop your own strategies and perspectives and find which sources of information work best for you. No one single person can monitor all AI developments, given the overabundance of content and opinions out there. The best approach as a worker is to follow your own interests and build a culture of sharing what you learn with your colleagues. Leaders should openly encourage dialogue and sharing among workers.

As blogger Shawn Maust writes, “In life, there are many things we have absolutely no control over—just like the surfer doesn’t control the waves. But we do have control over how we interact with whatever comes our way” (shawnmaust.com/2015/09/why-surfing-is-a-metaphor-for-life). The AI waves are here, and they will keep coming as the technology evolves. It’s time to grab our boards and paddle out, using low-barrier, human-centered approaches to foster a culture of inquiry and free up time for overburdened staff.

|