|

FEATURE

Informing Your Strategies With Scenario Planning

by Daniel W. Rasmus

| Scenario planning constructs plausible futures informed by today’s uncertainties. |

Strategies fail when those telling the story lose control of the narrative. When I was 11, my sixth-grade teacher walked our class to a local library, where I started writing my story. I learned about museums and natural history; to this day, I enjoy collections of fossils and shells indexed and displayed in cases and am inspired by books I checked out from that library. Unfortunately, as much as the influence of that small library in Carson, Calif., reaches through time to still touch me decades later, it closed in the 1990s. At some point, that library could no longer substantiate a story of value amid shifting economics, changing demographics, and a misalignment with the politics of place.

Strategy often fails when it encounters a bleaker future than imagined or a more progressive one. In a bleaker future, organizations fail to consider what they could or should cut under increasing budget pressures or negative political situations. They are ill-prepared to navigate a future that challenges fundamental assumptions about libraries and their purpose. Conversely, if the future turns out better than imagined, libraries may prove unequipped to capitalize on the windfall.

Libraries can avoid strategic failure by integrating scenario planning into their strategic-planning process. Scenario planning constructs plausible futures informed by today’s uncertainties. As teams define key uncertainties, they assign values that shape scenario narratives. Scenario planning’s intentional fiction articulates the future in ways that go beyond spreadsheets filled with what-if calculations to support alternative budgets and staffing plans or lists of proposed procurement and program cuts.

Scenarios place libraries in a larger context. Combined with strategic planning, they inspire transformational thinking, identify emergent risks, and help ensure that libraries are not caught flat-footed when new opportunities or threats arise. Scenario planning allows libraries to imagine alternative futures and anticipate actions and contingencies should those futures, or similar ones, surface.

Five Tips for Effective Scenario Planning

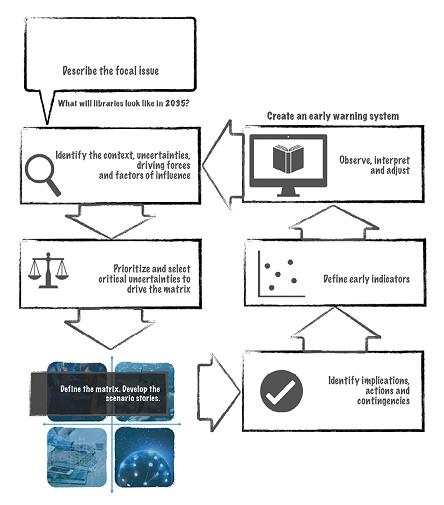

I have covered the basics of scenario planning in these pages before (September 2024, January/February 2023, and December 2023). The accompanying diagram (right) offers a high-level overview of the process. Some libraries have engaged in scenario planning or are maybe considering it. I offer five tips to help ensure that scenarios become a strategic tool, not just an exercise. I have covered the basics of scenario planning in these pages before (September 2024, January/February 2023, and December 2023). The accompanying diagram (right) offers a high-level overview of the process. Some libraries have engaged in scenario planning or are maybe considering it. I offer five tips to help ensure that scenarios become a strategic tool, not just an exercise.

Tip 1: Define the Scope

Scenario projects require a defined scope big enough that the strategic topic emerges from the narrative rather than driving it. For instance, working with libraries, I guide them to avoid asking, “What will libraries do in 2035?” While comfortable and seemingly attainable because of ready access to the issues and insights of libraries, it does not stretch the canvas, and it does not place libraries in a larger context.

I maintain a set of scenarios on the future of work, which I adapt to serve libraries. Being a librarian or working in a library is a type of work that’s subject to all of the forces of change related to other work experiences. I also argue that most people who visit a library or use its services live in the greater context of work in its broadest sense, even if some of that work is unpaid. In addition, libraries are centers for those who are seeking work. Together, we add the uncertainties related to the future of libraries to those that shape the future of work narratives. Libraries become a specialization of the future of work scenarios, drilling into their domain, much as I have done with banking, healthcare, or manufacturing.

Tip 2: Think From the Outside In

Just getting the scope right isn’t enough. Scenario-building projects, even when conducted by professionals, often lean into the client’s desire to explore areas too closely related to their domain. Library projects too often focus on books and patrons, funding and publishers, technology, and the structures that support the library and its community.

Library-centric stories are important, and they will surface in world-building. However, the world must be large enough to give them purpose and motivation, such as how people learn, how people build and interact with communities, what people value, and how those realities do—and will—manifest in politics and social movements. The scenario process encourages outside-in thinking aimed at creating a context for more organization-specific considerations of strategy that purposefully avoid considering uncertainties over which an organization has control.

Tip 3: Downplay Disruptions and Discontinuities

Disruptions come in many forms, including social movements, political realities, and technological upheavals. Incremental planning processes don’t include recognition of disruptions and discontinuities such as an accelerating pace of change or its scope. Good scenarios should include stories that make people uncomfortable and force leaders to confront uncertainties that test their sensibilities or undermine a closely held hope or belief.

Avoiding disruptions and discontinuities does a disservice and retracts one of scenario planning’s most potent benefits: challenging assumptions. People may grumble at incremental plans that cut budgets or deprioritize programs, but they become afraid when elected officials shred policy, eliminate functions, or close branches—or when technology displaces staff or redefines engagement models. Being too cautious and optimistic makes for poor scenarios. Scenarios need not carry readers to a dystopia, but they should recognize if major events or changes to the social fabric could impact what it means to be a library or how a library functions.

Tip 4: Tie Scenarios to Strategy

Incorporating scenario planning into strategic planning strengthens decision making by stress-testing strategies against different conditions. It encourages leaders to challenge assumptions, identify blind spots, and develop flexible strategies that can be adjusted as circumstances evolve. A strategic plan describes intention and desire, direction, and early action—it sets a tone for the future. Strategy is always in the act of becoming. It is not a vision but a guide to achieving a vision. The strategic-planning process cannot end with a strategy; it must also facilitate the story of how an organization overcomes obstacles.

Beyond stress-testing strategic-planning ideas, scenarios act as the backup when the official future fails to materialize, imperiling the strategy. They offer a way to rapidly reconsider positions and options through familiar stories rather than through panicked brainstorming and reactive decision making. Scenarios provide a space to practice choices within alternative futures and should include contingencies that guide strategic dialogue as libraries navigate change.

Tip 5: Avoid Prediction

Even if the official future paints a consensus view of the future, libraries need to be cautious about suggesting that the vision is anything more than one possible future. A vision states intent and describes hope. By couching that vision within a scenario-planning framework, constituents can see that the vision is not a prediction but a choice of strategic options against a backdrop of uncertainty. It’s OK for organizations to admit they don’t know what the future holds. None of them do. Equally, they can demonstrate leadership by showing the hard work they participated in to land on their vision and the framework they will use to navigate the uncertain troughs and hills of the future as it unfolds.

Any organization that suggests it can predict the future—no matter how hard it tries or how much it invests—will always be wrong. What it can do is say, “We don’t know what the future holds, but we have a robust process for thinking about it.” Prediction is a trap that will do nothing but disappoint. Scenario planning offers foresight that can inform, even if the scenarios never arrive as articulated. Sometimes, anticipation will squelch poor choices, and sometimes, it will inspire bold moves. The trick is not to predict the future but to always be wrestling with it.

Making the Future Real: Next Steps

There are many other tips that could be offered, including engaging diverse perspectives, incorporating cross-disciplinary insights, and having patience with the iterative and adaptive scenario-planning process. The most important next step should be to bring scenario planning into your strategic-planning process. Even if your library cannot afford to build its own scenarios, it can work to localize a set of scenarios that will create a foresight capability that did not exist before.

Watching trends is a complementary, but ultimately exhaustive and unfulfilling, scurry through screen after screen of ideas and memes that never rise to the statistical level of an actual trend. Even for those trends that appear credible, discontinuities and disruptions can derail them—sometimes with dramatic and nearly immediate impact. Long-held expectations about institutions can be undermined, social norms reframed as pariahs, and funding expediently reallocated to meet emergent views of political correctness.

My childhood library was swept away because it lost track of its narrative, failing to reinvent itself for the realities of a strip center amid economic and demographic shifts. Scenario planning might not have saved the library, but it would probably have better prepared it to serve the changing market.

Scenario-driven strategic dialogue makes alternative futures tangible. Contributors see their insights shaping narratives. Those assigning uncertainty values witness how they influence the stories to dare and stimulate. Those who discern implications for the library’s business model, its stakeholders, and its communities feel like pioneers discovering new territory. Scenarios need to be part of every strategic conversation, and they need to be maintained and updated as current uncertainties find clarity and new ones appear.

Throughout human history, stories have defined our most profound ideas, such as describing our place in the cosmos and the ethics for how we should treat one another. We trust stories as the foundation for civilizations. We trust stories to inform us about the present. We should also trust stories to help us shape the future of libraries. By combining speculation with logic, scenarios craft plausible myths that guide us through uncertainty.

|

DEFINING THE KEY CONCEPTS

Strategic planning is the structured process by which organizations define their long-term objectives, assess internal and external factors, and determine the best courses of action to achieve their goals. It involves setting priorities, allocating resources, and establishing metrics for success. Strategic planning provides a framework for decision making, ensuring that an organization remains aligned with its mission while adapting to changing conditions.

Scenario planning is a strategic tool that helps organizations prepare for uncertainty by exploring multiple possible futures. Unlike traditional forecasting, which relies on linear projections, scenario planning constructs diverse narratives based on key drivers of change. These scenarios test strategic assumptions, uncovering risks and opportunities that might otherwise go unnoticed. By considering a range of plausible outcomes, organizations can build resilience and adaptability into their strategic-planning process.

Scenario thinking is a mental model that shifts decision making from reactive problem solving to a proactive exploration of possibilities. For individuals trained in developing and using scenarios, it becomes a way of framing uncertainty—not as a threat, but as a lever for strategic insight. Instead of seeking a single correct answer about the future, scenario-thinkers instinctively consider multiple plausible outcomes, recognizing that complexity and change are constants.

This mental model rewires default thinking patterns by moving beyond linear cause-and-effect reasoning. Scenario-thinkers learn to identify key drivers of change, assess interdependencies, and recognize weak signals that may indicate emerging trends. They also internalize the discipline of suspending assumptions, embracing ambiguity, and testing strategies across diverse futures. The result is a more agile and resilient approach to decision making, in which adaptability and preparedness replace rigid planning and reactive responses. |