|

EDTECH

Teaching TikTok to Help Counter Misinformation

by Laura Winnick

| Even though I’d never made a TikTok video, I was ready to bring the medium into my classroom. |

For the past 4 years, I have taught media literacy to students in grades 6–8. As a librarian media specialist, I hope to create a digital curriculum that is relatable, relevant, and rigorous. The foundation of my media literacy courses is to use media to be critical of media. This means that my curriculum is always evolving and is responsive to what is happening in the world and what is happening in my students’ lives. I also work at a project-based learning school, where we seek to teach skills through the creation of projects that have real-world audiences.

As my orientation to media literacy changes, the projects that my students create change too. Every year, I try to find new vehicles through which students can demonstrate their learning. In the past, students have created counternarrative videos that respond to dominant narratives in the media, collaged stereotypes of identities in the media, collaged self-portraits, edited and produced podcasts, used Canva to create digital designs, and created kinetic typography videos. Each of these approaches required me to familiarize myself with new technology. I love this aspect of being a librarian media specialist; I’m forced to learn by doing. With each new tech tool, I tinker in order to anticipate hiccups that my students might face when using it. I try to predict the ways I can scaffold the learning of a tech tool and make the technology more accessible to students.

Last summer, I began to reconsider my 8th grade curriculum. Given the impact fake news had had in our country recently—including the way it impacted the 2020 presidential election—I realized that I wanted to focus on misinformation.

Last year, with 8th graders, I created a kinetic typography misinformation video project, in which students were tasked with describing the five types of misinformation. The News Literacy Project defines these as satire, false context, imposter content, manipulated content, and fabricated content.1 The kinetic typography element was inspired by Apple’s advertisements.2

When I watched these videos, I realized how impactful a message could be, especially the quick succession of text arranged against an upbeat song. I wanted students to experience teaching and learning with this type of fun 21st-century connection. I knew students had seen these advertisements, so I was ready to push them to produce these videos.

Students mastered editing and producing video, most notably cutting and arranging text one beat after the other. Our school provides Chromebooks to students, so we used WeVideo for editing.3 The project demanded that students be focused and detail-oriented. Follow the link in the Endnotes section to see examples of the student videos about imposter, fabricated, and manipulated content.4 Although the project enabled students to digitally master video editing, the content was not as formative to the product. Students spent the bulk of their time editing and not necessarily deepening their understanding of misinformation. I wanted to change this. When planning for the next year, I decided to push my students beyond the work of their predecessors and have them analyze misinformation—not just state the type of misinformation. But we needed a project.

Over the summer, I had also become obsessed with Media-Wise’s TikTok.5 MediaWise is an organization that teaches media literacy skills to people of all ages. I first came across it on Twitter, and I loved how it was using its platform to educate young people about misinformation in engaging and relevant ways. I especially loved how it was equipping its MediaWise campus correspondents to make media; it’s clear these correspondents know how to produce TikTok videos that are compelling, informative, and appealing to Gen Z.6

I knew that in this next version of a misinformation project, I wanted to meet my students where they were. I wondered if I could teach them to make TikTok videos similar to the aforementioned ones. Even though I’d never made a TikTok video, I was ready to bring the medium into my classroom. It was my goal to teach students to use social media so that they could critique the content that was coming across their own newsfeeds, using TikTok to fight back against misinformation on TikTok.

This is a unit that I taught to 8th graders over the course of one semester, for 15 classes total; Media Literacy meets weekly for 45 minutes. This unit can be taught in a condensed 3-week unit in a humanities class; it would fit in well with a unit on credibility and sources. The essential questions were as follows: What is misinformation? What are strategies to combat misinformation? How might we educate our community using TikTok? How do we create a TikTok video that combats misinformation? The goals were for students to use strategies to evaluate whether viral content is misinformation, write a script, make revisions on that script, and create and produce a TikTok video.

DEBUNKING FALSE CLAIMS

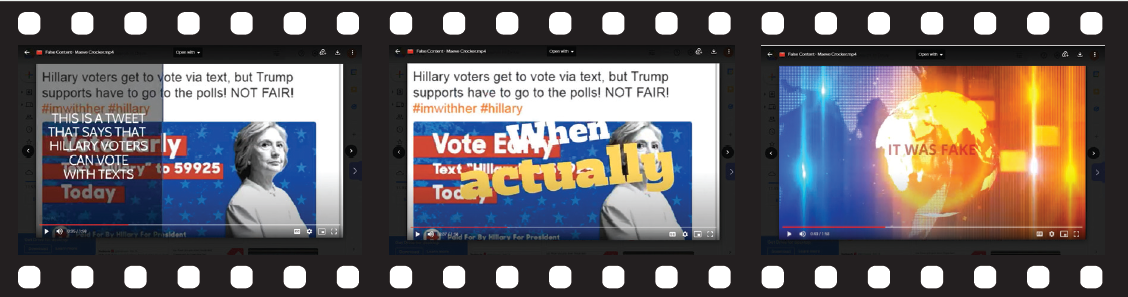

Previously, students used a technique called kinetic typography—which flashes words across the screen set to a heavy backbeat—to discuss misinformation, how to spot it, and how to debunk it, as these stills from their videos demonstrate.

In the first week, we spent most of our time identifying and using strategies for misinformation. There were many resources for identifying whether news is fake or real—so many that it was overwhelming. After compiling the ideas, I decided to teach the following strategies: CRAP test, SIFT test, reading upstream, reverse Google Images search, pause to verify, and fact-checking. These strategies were compiled from the News Literacy Project, several libguides, and MediaWise. I selected these based on how useful I found them, my sense of what students would be interested in, and the ease with which students could teach them to their peers. Ultimately, students had the ability to select which strategy they were most interested in. When student choice is at the center of a project, I like to provide an array of options, so that students can dig in and find something they connect most to.

The second week was devoted to finding viral news. I used Snopes to let students locate examples themselves.7 They loved using this resource; it’s user-friendly, fun to scan, and very relevant to students’ lives. A hurdle was making sure that Snopes’ URLs were not blocked on the school’s Wi-Fi

network. I worked with our school’s tech team to make sure that these sites weren’t blocked during our class, so that students could freely explore them. I have found that when bringing in content from popular social media outlets, I often have to double-check to make sure the content can be streamed on the school’s Wi-Fi.

PROJECT CRITERIA

The student’s TikTok videos needed to do the following:

- Fully explain a strategy for identifying misinformation

- Show an example of viral fake news

- Use the strategy to debunk the viral fake news

- Include captions

- Include background music/sound

- Be under 3 minutes

|

One difficulty with teaching students about fake news is that after the news is determined to be fake, it is usually taken down from the internet. It becomes harder to find! This is constantly an issue in teaching about fake news. Beyond Snopes, my other resource for locating misinformation was the News Literacy Project’s newsletter, The Sift, which collects examples of viral fake news and debunks them.8 This resource was exceedingly important to me as I continued to provide students with examples of misinformation in the real world. Most days, the lesson began with me sharing an example that had been featured in The Sift and talking with students about how it had been debunked.

At the end of the second week, I played MediaWise’s TikTok to show students what their final products needed to be. Together, we watched and analyzed 10–15 videos, identifying the key parts of each video and parsing the elements that they would be required to create themselves. We also read and annotated MediaWise’s sample script about Sen. Rand Paul and the vaccine, so that students understood what they were being asked to write.9

I created a template of elements and supplemental text.10 It was important for students to realize when they needed to show other media on the screen (such as the viral news, in the form of a tweet or Instagram post). There were several project checkpoints in this unit. To start, students needed to pick a strong example of viral news. I allowed them to select news that they could prove to be real in an effort to support student choice. I reviewed these before letting students choose what strategy they were going to use to debunk it. Students needed to show that they understood how to use the strategy. The next checkpoint was the script. Several groups required several edits. Most students had to be reminded to provide context about where the viral news was coming from, the user who created it, and why it mattered. The final checkpoint was the rough draft of the video.

As an educator, I found two parts of the project to be really difficult. The first was making sure that students divided the workload equally, and the second was ensuring high-quality final videos. Most students ended up using their personal phones to film and edit the video, and it was difficult for more than one student to use the device at a time. Students had the option of using an iPad or my phone to film the video. In the end, no one opted to use the iPad. I also let students edit the video on WeVideo if they wanted to, but most of them stuck to TikTok because of their familiarity with the technology.

There are positives to having students use their own devices: They are very familiar with them, require no support in navigating them, and get excited about using their cellphones, which is usually not allowed during school hours. The negatives include the fact that not every student has their own device, and only one student can use a phone at a time. This made editing tricky, in that one student ultimately took the reins of the project and drove the editing process. Also, to ensure students created high-quality videos, I reviewed each student video and ultimately gave one-on-one feedback to make small changes.

Although using TikTok was exciting, I found these issues to be more related to project-based learning than the technology/medium itself. When assigning group projects, there are often issues related to equity and division of labor. Similarly, when ensuring high-quality videos, I found that I needed to instruct the students on how to make small changes to ensure that their videos were at the same level as MediaWise’s campus ambassadors’ videos. Students were required to make videos that explain a media literacy tip for dealing with fake news and were featured on our school’s Instagram. The final videos can be found by following the link in the Endnotes section.11

Surprisingly, the students were most plagued by the closed captions. Some students ended up not publishing captions on their videos because of tech issues. When students used TikTok’s auto-captioning feature, they had to review every line with a fine-tooth comb. There were a lot of caption snafus, which students found irritating.

How did my students feel about bringing TikTok to the classroom? It was a mixed bag. Their comments included, “It felt weird, like mixing parts of our lives. I did not like it,” “We don’t usually use social media in school. It was a little weird but I enjoyed it!” “It was new but useful,” “It was a new experience, but it felt pretty easy since I am used to social media,” and “I thought it was fun because I had never done it before and it was fun to do a more independent project!”

|