|

FEATURE

Verifying the Direction of Website Design

by Michael Crane

| New initiatives in outreach and instruction and the supporting redesign of our website led to a remarkable 250% increase in website visitation. |

In fall 2019, the U.S. Air Force Academy’s (USAFA) McDermott Library directed staffers to solve a problem with student engagement. The average visitation to our library website was nearly half the rate as at comparable libraries, such as the U.S. Military Academy (West Point). A research study was needed to identify and address the underlying cause, and we were able to resolve it. Student engagement with USAFA’s library website went from 40,000 visits in 2020 to 100,000 visits in 2022. This study is being shared in hopes that other libraries will find some useful insights in our research approach.

Designing the Research Study

There are four research questions we faced when updating our website.

- Why is our website not being used?

Let us ask using interviews and surveys.

- What on the website needs to be updated?

Let us observe students’ behavior navigating the website and identify exactly where their progress breaks down.

- What designs work best for our students?

We can compare how our students interact with different design features, so that we can pick what works best.

- Did our design changes help?

After updating the website in 2021, we can use the same methods to compare our library website in 2020 with the one in 2022.

Perhaps this study sounds like something only a university can accomplish with dedicated IT help, but I assure you it is within reach for smaller institutions. We have 4,000 undergraduate students at our academy, learning from 228 faculty members across 32 majors. Our single library has 34 staffers and manages an on-site collection of 500,000 materials and 80 online databases. Data collection and analysis required one team lead and two to three assistants each year to help with 41 student observations and two surveys.

Observing Students’ Use of the Website

One of the goals of this research was to have easily comparable metrics that showed a clear difference between design choices. To do this, we used the variables of time and failure rate. At the beginning of an observation session, a student would be given six things to locate, which were:

- A provided book title

- A provided article title

- A librarian

- Online audiovisual or ebook material for a specified class assignment

- General help on an academic topic to the point where you are satisfied

- A way to request a book that the library does not have

Starting at the provided library homepage, students could complete these tasks in any order using a laptop or mobile phone. Clarifications were provided, such as completing the tasks was not a race, struggling or giving up on a task was perfectly fine, and their feedback would help us select design features that would benefit all of their fellow students.

The duration to complete each task was timed. This revealed which design features were the easiest to use and the most intuitive (with faster completion times) and which may have needed adjusting (slower times, increased failure rate). Some tasks were completed as fast as 5 seconds, while others lasted as long as 5 minutes. Overall, the process only took 15 minutes of the student’s time, with another 15 minutes available for discussion and feedback.

These metrics serve as a foundation for comparison, but they require different websites for the students to try. Before the study, we curated a list of comparable library websites cited by literature and design experts in 2020. When students arrived for their session, they were presented with a choice: “Which library website would you like to try today?” This approach turned the activity into a fun exploratory endeavor, and the students became fully engaged and provided useful feedback.

Metric Analysis

The data from comparisons immediately showed design advantages from different selected library websites. The website of Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University (BYU) had a very fast interface for finding different material types. When it came to help with a topic, though, our students struggled. The websites of Caltech Library at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and Fondren Library at Rice University had faster times and lower failure rates for help with a topic, so we looked at their designs and how they differed from BYU’s and our own. These and other observations focused our pathfinding analysis; in combination with student feedback, this allowed us to capture which design features were successful and why. What was different in the help-with-a-topic search? All the previously mentioned websites used the phrases “Research Guides” or “Library Guides.” These phrases were not universally recognized. Both the Caltech and Rice libraries provided brief explanatory language, such as “by subject” in an expanded menu view or an intermediary page with a list of selectable academic subjects. They clarified what was unfamiliar to the student.

Why Are They Not Coming? Student Feedback

Libraries are wonderful places, and we seek to help students get the most out of their experience. So why was our library website not being used? We needed to abandon our preconceptions and let students talk about what they liked and disliked at our library and others. What do they value at the library? We used a combined approach of a student survey and interviews as an exploratory method to capture as much data as possible. As it turned out, this strategy did find external factors affecting student engagement.

We learned that students who were busy studying in the fields of basic sciences and engineering only saw the library as a place to study, not as a place to do research. We checked with the relevant faculty members, and there was concern about the research skills these students were developing. Learning these factors made our mission clear: We needed to revitalize our library outreach and instruction.

Applying Research Results

In the 2021 academic year, we redesigned our core library orientation for all incoming students. Our instructional librarians collaborated with faculty to teach 85 new classroom sessions and five new writing workshops, and we redesigned our homepage to make it clear there are librarians and resources available to support all majors.

As our quick-link buttons performed faster than alternate designs, they were expanded. We also learned that our students relied heavily on the top navigation bar, and we designed it to make it consistent across the homepage, supporting subject guide and service pages, the OPAC catalog, and our discovery platform. Selecting a librarian and helpful resources became clearer with the addition of broad academic categories on the homepage. These were tied to a reorganized navigational layout by academic subject for guides and databases.

The pandemic and a temporary switch to 100% virtual service also served as a motivator to fully implement a library-chat feature and a robust library answers/FAQ system.

What Design Changes Worked?

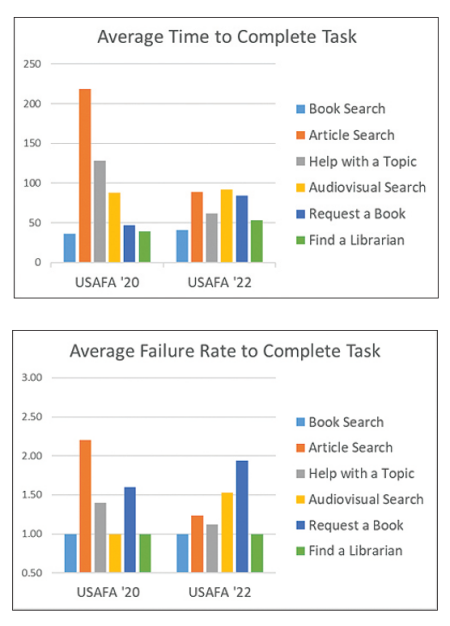

In 2022, we repeated our survey and observation study using the same metrics from 2020. How do the metrics compare after a year with our new website and outreach initiative?

- Switching our primary search bar to a Google-like discovery system—This improved by 200% article search task speed and success rate.

- Adding academic-field terminology and by-subject language in navigation—This improved by 150% the time and success rate of help-with-a-topic results.

- No clear distinction between items available online versus on the library shelf—Searches for audio, visual, and ebook materials had a 50% increase in failure rate.

- Swapping “Request a Book or Article” to “Interlibrary Loan”—This yielded the most interesting result. When our design committee reviewed our 2020 findings, this suggestion was made: “We are doing all of this instruction and outreach, what if we teach students what interlibrary loan means? This term is more accurate than request a book or article.”

Having a 2022 post-test of our 2021 revised website allowed us to be experimental, including abandoning assumptions that library language was too technical for incoming secondary school students. Did using the term “interlibrary loan” work? It did not, but it did allow data to be collected that showed students associate a given task with a specific word or phrase they had learned. Each student has a conceptual mental model of words and search behaviors that have worked for them previously. Having a 2022 post-test of our 2021 revised website allowed us to be experimental, including abandoning assumptions that library language was too technical for incoming secondary school students. Did using the term “interlibrary loan” work? It did not, but it did allow data to be collected that showed students associate a given task with a specific word or phrase they had learned. Each student has a conceptual mental model of words and search behaviors that have worked for them previously.

This mental model varies for each student. Some of the tasks we tested relied on a single phrase in website navigation—such as “Interlibrary Loan” or “Research Guides”—to reach a destination. If the phrase was not recognized, this caused the potential for failure. Other tasks had a variety of similar words available, such as “By Subject,” “Subject Guides,” and academic categories. This technique is known as a “synonym ring.” Multiple phrases in navigation led to an increased chance of recognition from diverse mental models. What if we abandoned the concept that there is only one best universal word or phrase and allowed a more varied strategy in navigation paths for students to find assistance? Would our website be more broadly accessible to students with diverse backgrounds? Our study suggests the answer to that is yes.

Additional Findings

- In both 2020 and 2022, our students would search the library website for educational support services.

- Consistent top-level navigation reassured students they were still in the library and not somewhere else. This was the most-liked feature.

- Chat support was most desired when a student became stuck, such as during a failed discovery search.

- Students wanted to know if the person they were asking for help was an expert in the academic field they were asking about.

- Those coming out of secondary school or public library backgrounds do not know what makes an academic library different.

- A librarian’s instruction helps a student remember a process, but not technical library phrases.

- A librarian’s instruction teaches how the library can help in useful new ways.

- How a library can help a student in their field of study is a key to whether they will make use of the library.

Looking Into the Future

We believe this study showed that testing a variety of designs and comparing their performance quickly identified design features that our students liked. Planning a post-test using the same metrics allowed for greater experimentation and a direct comparison of design-change effectiveness, and it established a benchmark for smaller, iterative, more-targeted changes. Most importantly, it verified for us what works. Incorporating a check for external factors revealed areas in which faculty member outreach and instruction could be improved to the benefit of our students. New initiatives in outreach and instruction and the supporting redesign of our website led to a remarkable 250% increase in website visitation.

We have planned updates in 2023 to fully implement 2022 findings for our website and hope to look more closely at whether a synonym ring approach to available navigation pathways performs best. Strong themes in the data emerged that designing clear pathways to academic subjects and core skill development are useful directions for academic library website design. All of these conclusions were made possible by a great research team and all of the staff and students at USAFA who contributed their time and energy to this study. We hope these findings will help and inspire you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions.

|