FEATURE

For Future Tech, Look to Assistive Design

by Suzanne S. LaPierre

| Innovations for people with disabilities frequently end up expanding and improving options for everyone.

|

We're not very good at predicting the future, but sometimes we get it half right. The future of automobiles turned out to be self-driving cars, not flying cars. Rosie, the Jetsons’ aproned robot maid, turned out to be Siri, the disembodied virtual assistant. Plans to replace library bookshelves with laptop counters became outdated when smartphones surpassed laptops as the preferred mobile devices. While ebooks are here to stay, it turns out paper books are sticking around too. As flawed as enterprise future-gazing may be, one area that has been predictive in the past is assistive technology that’s designed for the diversely abled. Innovations for people with disabilities frequently end up expanding and improving options for everyone.

Assistive Design Goes Mainstream

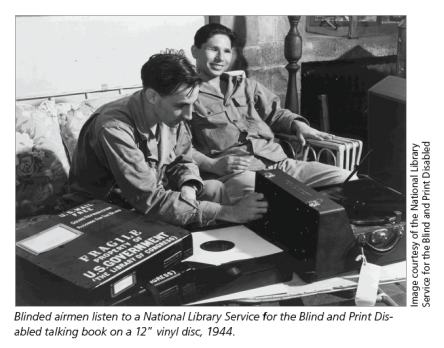

The LP record was invented as a means of fitting book-length content into audio format for the blind.1 Shorter records were fine for songs, but audiobooks required more storage. Eventually, the LP became a standard length for music albums, shaping our concept of curated collections of songs branded by cover art. And while audiobooks were originally developed for those with blindness or low vision, they are currently a format preferred by commuters, joggers, and many other readers. The LP record was invented as a means of fitting book-length content into audio format for the blind.1 Shorter records were fine for songs, but audiobooks required more storage. Eventually, the LP became a standard length for music albums, shaping our concept of curated collections of songs branded by cover art. And while audiobooks were originally developed for those with blindness or low vision, they are currently a format preferred by commuters, joggers, and many other readers.

The board game Candy Land was invented by schoolteacher Eleanor Abbott, who had polio as an adult. Treated in a ward full of pediatric patients, she became intimately familiar with the suffering of children confined in iron lungs. She invented a game to set them free, at least in their imaginations. The boy pictured on the original board game is wearing a leg brace as he embarks on his fanciful journey. “Candy Land’s play revolves around movement. In theme and execution, the game functions as a mobility fantasy. … Every card drawn either compels you forward or whisks you some distance across the board. Each turn promises either the pleasure of unencumbered travel or the thrill of unexpected flight. The game counters the culture of restriction imposed by both the polio scare and the disease itself,” Alexander B. Joy writes in The Atlantic. 2

While the game served its purpose by providing mental activity and a sense of movement for disabled children, it turns out that many others respond to the same stimuli. The fantasy adventure’s key components—the child as protagonist, a design that simulates movement, and the luck elements that allow even the youngest player to win—became features for many games to follow. The iconic Milton Bradley game remains popular for children a little more than 7 decades later.

Among other ideas for people with disabilities that went mainstream were text-to-speech and speech-text technologies. Both technologies were developed largely because of their usefulness to people with disabilities. In 1998, Kurzweil won a Stevie Wonder Vision Award for Product of the Year for its pioneering text-to-speech reading machines. The first of these, in 1976, was the size of a dishwashing machine. Now the technology is in standard use via voice assistants, such as Siri and Google Assistant.

What makes design for the diversely abled so predictive of future developments? It turns out that we all enjoy flexibility and ease of use. Features that are needed by users with certain disabilities may also be desired by other users. While the percentage of people requiring a particular product may be small, the percentage desiring the option may be large. We all have limitations, both as a species and as individuals. There are limits to how much freedom we have, to our strength and agility, and to the quality of our communication skills. Our imaginations and aspirations might soar, but the human body can only do so much. Technologies designed to help people with disabilities speak to the universal desire to do more things more easily.

Future Technologies

Whether it’s the secret decoder ring in the 1930s or the Apple Watch in the 2020s, we seem to want to hold the world in the palm of our hands. The fantasy—swiftly becoming reality—is commandeering one small device that’s capable of answering our questions, solving our problems, and doing our bidding. What if such devices could be activated by a glance or a thought?

Mind-activated and sight-activated products may have raised Big Brother alarms if they were developed for mainstream use, but no one can argue their usefulness as medical products for the disabled. Brain-computer interface (BCI) is the technology used to translate brain signals to computer commands, allowing people who have neuromuscular disorders to manipulate cursors, robotic arms, prostheses, wheelchairs, and other devices. For those with severe disabilities and their loved ones, BCI technology offers the possibility that those who are unable to speak or use their limbs may soon be able to communicate or operate assistive devices for movement.

As BCI technology becomes more accurate, portable, and affordable, it may become useful for augmenting human performance in a variety of professions. One can even imagine implications for the gaming world. International researchers are currently working on making BCI devices more portable and comfortable to wear. 3

Of the innovators highlighted in MIT Technology Review’s latest “35 Innovators Under 35” feature, 14 are working on technologies related to health science, including skin-worn medical sensors (one powered by sweat), more sensitive and functional prosthetic limbs, and simpler and more accurate diagnostics and therapies. 4 Better prosthetic limbs for humans may revolutionize bionic arms for robotics, and skin sensors developed for those with health problems may soon power fitness devices for athletes. Visuals resulting from current radiology and healthcare imaging technology have even inspired the world of fine art. 5

Universal Design vs. Assistive Technology

Universal design and universal access are key concepts these days. Designing spaces and technology tools to work for everyone is critical. Ramps are used by stroller-pushers as well as wheelchair users, and automatic doors help people with arms full of books as well as people on crutches. However, some folks still need a wheelchair to get up the ramp. In other words, universal design doesn’t completely replace the need for assistive technology or vice versa. As with stairs and elevators or e-readers and paper books, a variety of tools and technologies expands access and options.

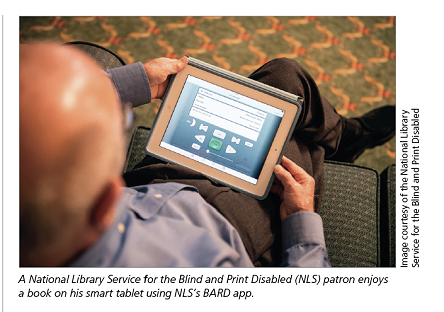

Many sighted people assume that Braille is no longer needed now that we have audiobooks and text-to-speech technology. However, Braille is “at the heart of literacy” for many blind readers, just as printed books are for many sighted readers, according to Kristen Fernekes from the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS). In addition to continuing to provide traditional Braille materials, NLS is piloting an effort to make refreshable Braille display available via libraries. Refreshable Braille converts information from a computer screen into Braille via pins that can be read manually. Commercially available audiobooks aren’t a universal access solution because non-text visual elements (charts, graphs, maps, and illustrations) aren’t usually described in them. The NLS relays these additional elements in audiobooks for use with its BARD app. BARD books also include descriptions of material such as reader’s guides that generally aren’t included in commercial audiobooks. 6 Many sighted people assume that Braille is no longer needed now that we have audiobooks and text-to-speech technology. However, Braille is “at the heart of literacy” for many blind readers, just as printed books are for many sighted readers, according to Kristen Fernekes from the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS). In addition to continuing to provide traditional Braille materials, NLS is piloting an effort to make refreshable Braille display available via libraries. Refreshable Braille converts information from a computer screen into Braille via pins that can be read manually. Commercially available audiobooks aren’t a universal access solution because non-text visual elements (charts, graphs, maps, and illustrations) aren’t usually described in them. The NLS relays these additional elements in audiobooks for use with its BARD app. BARD books also include descriptions of material such as reader’s guides that generally aren’t included in commercial audiobooks. 6

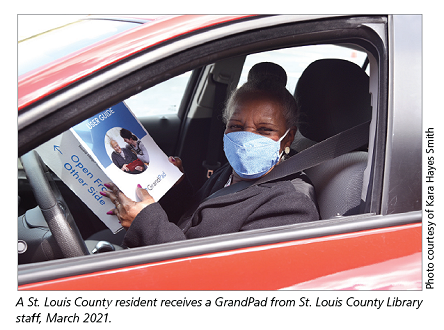

However, commercial enterprises are also investing in assistive technology. The GrandPad was designed for the growing demographic of adults age 75 or older. It includes a charging cradle that eliminates the need for cords, built-in wireless data connectivity, large front-facing speakers for clearer audio, easy-to-see icons, and a 24/7 live help button. The St. Louis County Library in Missouri used Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funds to purchase and deliver 1,500 GrandPads to adults age 75 or older who were isolated by the pandemic.

The New York Public Library (NYPL) offers community tools and training in the creation of tactile graphics and objects. Tactile graphics are maps, diagrams, and images embossed into paper that can be felt manually, enhancing the reading experience for blind or low-vision people. NYPL equipment includes a Braille embosser, computer-aided design (CAD) software, 3D printing pens and a 3D printer, tactile drawing tablets, binding machines, a Swell-Form Graphics machine for creating raised and textured inkprints with color elements, and Sensational BlackBoards for raised-line drawing on regular paper. Such technology might also be used in art, self-publishing, and presentation design.

The Future of Libraries

The expectation for universal design in such entities as software and architecture is bound to continue. The desire for portability, ease of use, and automation is also likely to influence the direction of library services. Portability will continue to be important as people expect instant access to information from wherever they are. Portable—even wearable—access to the catalog may become more user-friendly, enabling voice requests for audiobooks and ebooks or guiding users through physical stacks.

Conversely, the library as a physical place will increasingly be needed to balance a more virtual society. Libraries play a critical role as community hubs. As more of our lives go remote—and fewer people work in a traditional office or classroom—many rely on the library as a workplace and meeting place. “Working from home” means “working at the library” for people who need separation of their work and home lives.

Many public libraries are grappling with new overlaps between physical and virtual space—and even physical and virtual people. As more meetings take place virtually, individuals engaging in in them increasingly request meeting rooms that are traditionally reserved for in-person groups. Does a person virtually joining a meeting via Zoom count as a person for the purposes of reserving a group space? We are having to rethink the dividing line between our physical and digital selves. Many public libraries are grappling with new overlaps between physical and virtual space—and even physical and virtual people. As more meetings take place virtually, individuals engaging in in them increasingly request meeting rooms that are traditionally reserved for in-person groups. Does a person virtually joining a meeting via Zoom count as a person for the purposes of reserving a group space? We are having to rethink the dividing line between our physical and digital selves.

While BCI may not become the norm this century, ease of use is a criterion that should extend to all library services. Whether it’s downloading an audiobook, scanning a document, or booking a meeting room, frustration brought on by design that isn’t user-friendly leads customers to give up on the library or have negative feelings associated with their experience. New equipment is welcome when it brings new possibilities, but not when it’s so confusing for patrons that staffers spend most of their time working as personal tech assistants. We should expect and demand user-friendly interfaces that are accessible for all community members—disabled or not, tech-savvy or Luddites.

Future developments don’t necessarily erase that which came before. While many designs and technologies do become obsolete, the result of change is often that we have more choices. Elevators didn’t replace stairs, smartphones didn’t replace desktops, and ebooks didn’t replace paperbacks. We just have more options.

While many elements of libraries change with the times, others remain because they speak to core human needs and desires. Just as the physical space of the library serves as an anchor for the community, so do other defining elements (such as tangible books and humans who pick up the phone or interact face-to-face). We should strive to maintain these aspects that are the soul of the library, even as virtual options expand. The experience of walking among the stacks, picking up a book, leafing through it, and serendipitously crossing paths with a neighbor—that is Candy Land for readers.

|