FEATURE

Checking In With Google Books, HathiTrust, and the DPLA

by Naomi Eichenlaub

| Big developments over the past 12 months have included the launch of the DPLA, a partnership between HathiTrust and the DPLA, [and] a settlement between publishers and Google Books ... |

Google Books and HathiTrust have been making headlines in the library world and beyond for years now, while a new player, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), has only recently entered the scene. This article will provide a “state of the environment” update for these digital library projects including project history and background. It will also examine some challenges common to all three projects including copyright, orphan works, metadata, and quality issues.

Google Books

Let’s begin with a bit of background on the Google Books project, which was officially launched in October of 2004 at the Frankfurt Book Fair. The Google Print Library Project, also known as Google Book Search, was announced 2 months later in December 2004. It included partnerships with a number of high-profile university and public libraries, including the University of Michigan, Harvard University, Stanford University, the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, and The New York Public Library. The project quickly became controversial because of Google’s plan to digitize not only works in the public domain but also titles still under copyright. Within a year of the project’s launch, two lawsuits were filed against Google: a class-action suit on behalf of the Authors Guild and a civil lawsuit brought forward by the Association of American Publishers (AAP). Despite the controversy surrounding Google Books, in 2006 and 2007 additional libraries announced partnerships with Google. In 2006, these included the University of California system, the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the University of Virginia, and the Complutense University of Madrid, which became the first Spanish-language partner for the project. In 2007, eight more libraries joined including libraries in Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and Japan, as well as the University of Texas–Austin, Cornell University, and Columbia University.

In October 2008, a hefty settlement decree hundreds of pages in length and worth $125 million—which would eventually be rejected—was announced between Google, publishers, and authors in response to both lawsuits. The settlement would permit Google to sell entire books, offer subscription access to the full database, and allow up to 20% of the book to be viewed for free. In 2010, Google announced that it would launch a digital bookstore to be called Google Editions with all content hosted online in the cloud. At this point, Google had scanned more than 12 million books. This was also the year that it made the ambitious proclamation that it intended to scan all known existing books by the end of the decade, which, at the time of the announcement, numbered just less than 130 million.

In March 2011, a federal judge rejected the 2008 settlement on the basis of multiple objections. One year later, Google had scanned approximately 20 million books. In October 2012, Google and AAP finally reached a settlement in their 7-year copyright dispute with an agreement that allows users to browse up to 20% of a book’s content and purchase digital copies through the Google Play service. At the time of writing this article, the legal dispute with the Authors Guild is still outstanding. However, a July 2013 development in the case saw a ruling that the Authors Guild’s lawsuit cannot proceed as a class-action suit and that another trial is needed to determine the validity of Google’s assertion that displaying excerpts or snippets of whole books online should be deemed Fair Use under U.S. copyright law. As of the time of writing, the Google database was rumored to contain approximately 30 million scanned books.

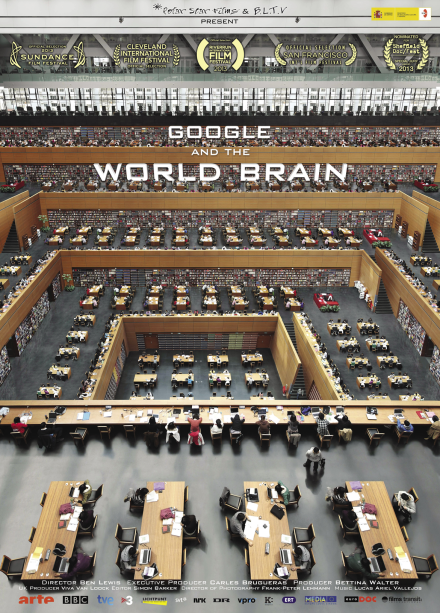

Google and the World Brain

Making the rounds as an official selection for a number of film festivals in 2013 is a documentary about the Google Books project titled, Google and the World Brain, which is a reference to the H.G. Wells book published in 1938. The film, produced by Polar Star Films and B.L.T.V. and directed by Ben Lewis, is a Spain-U.K. co-production that premiered in January 2013 at the Sundance Film Festival. It also won Best Documentary at the Rincón International Film Festival in Puerto Rico in May 2013. It tells the story of the Google Books scanning project saga, which the film’s website describes as “[t]he most ambitious project ever conceived on the Internet” and which the trailer describes as “[a] battle between the people of the book and the people of the screen.” Framed from a vantage point that definitely leans toward depicting Google as an evil entity, the film illustrates the potential dangers inherent in Google’s plan to scan the universe of knowledge. The reviews are favorable, and you can check the website (worldbrainthefilm.com) for a list of screenings near you.

HathiTrust

With Google scanning millions of books from the collections of research libraries, an inevitable question arose: What will happen to the scanned collections of the Google Books library partners if Google disappears?

Enter HathiTrust. HathiTrust Digital Library began in October 2008 as a collaboration of the 12 universities of the Committee on Institutional Cooperation (CIC), the University of California system, and the University of Virginia. According to the HathiTrust website, the focus of the initial collaboration was “preserving and providing access to digitized book and journal content from the partner library collections,” which included materials digitized by Google, the Internet Archive, and Microsoft (both in copyright and public domain materials), as well as works digitized locally through in-house initiatives. It allowed institutions to build a repository to preserve and distribute digitized collections and develop “shared strategies for managing […] digital and print holdings in a collaborative way [in order to] ensure that the cultural record is preserved and accessible long into the future.” Today, there are more than 80 institutions participating in the project, and membership is open to institutions worldwide.

In terms of content in HathiTrust, we know that while Google scanned the contents of a number of large research libraries, Google also contains a large number of trade and more popular titles as well. According to an overview handout published by HathiTrust, “Many works that are available in HathiTrust are not present in Google Books because they were not digitized by Google, or not available in Google Books because of differing rights determination processes. The largest categories of these include U.S. federal government documents and public domain works published in the United States after 1923.” HathiTrust also asserts that its subject representation is similar to any large North American research library, and it approximates that it holds digital versions of roughly 50% of the print holdings of every large research library in North America. Data visualizations on its website show graphical representations of subject coverage of the collection by the Library of Congress call number, as well as language and date coverage for the collection. At the time of writing, HathiTrust hosted more than 10.7 million total volumes and more than 5.6 million book titles.

According to HathiTrust’s overview handout, in terms of its copyright status, its content is approximately 68% “in copyright” and 32% in the public domain. Of that 32% in the public domain, 21% is public domain worldwide (of which approximately 4% comprises U.S. federal government documents), and 11% is public domain in the U.S. Approximately 12,000 volumes or 0.1% of the content is licensed as open access (OA), including Creative Commons-licensed materials. To clarify, when HathiTrust uses the term “public domain” worldwide, it means in the public domain for anyone anywhere in the world. In general, these are texts that were published in the U.S. prior to 1923 or published outside of the U.S. before 1873. It also includes U.S. federal government documents. The public domain in the U.S. documents are only available from U.S. IP addresses.

‘ The time is close at hand when any

student, in any part of the world, will

be able to sit with his projector in his

own study at his or her convenience

to examine any book, any document,

in an exact replica.’

—H.G. Wells, World Brain, Metheum & Co. Ltd., London, 1938 |

|

| Movie poster for the documentary that depicts Google as doing no good |

Digital Public Library of America

The DPLA, launched in the spring of 2013, is building a national digital library that will collocate the metadata of millions of publicly accessible digital assets. Conceived by Robert Darnton of Harvard University, in part as a response to the more commercial Google Books endeavor, the DPLA aims to unify previously siloed large collections such as the Library of Congress, the Internet Archive, and various academic collections as well as to collocate the metadata of smaller institutions and historical societies. In an article for The New York Review of Books in April 2013, Darnton described the goal of the DPLA as “to make the holdings of America’s libraries, archives, and museums available to all Americans—and eventually to everyone in the world—online and free of charge.”

According to Darnton’s article, the DPLA comprises a distributed system of content hubs and service hubs, where the former are “large repositories of digital materials” and the latter are physical centers that will help “local libraries and historical societies to scan, curate, and preserve local materials.” In June 2013, the DPLA announced a partnership with HathiTrust—one of its newest and largest content hubs with the addition of more than 3 million ebooks.

Moreover, the DPLA describes itself as a platform that facilitates “new and transformative uses of […] digitized cultural heritage” with an “application programming interface (API) and open data [that] can be used by software developers, researchers, and others to create novel environments for learning, tools for discovery, and engaging apps.” Ultimately, the DPLA could link with national collections around the globe. In fact, the DPLA infrastructure was designed to be interoperable with the Europeana cultural database, an aggregator of the digital cultural collections of more than 2,200 institutions across Europe. Darnton envisions that “[w]ithin a generation, there should be a worldwide network that will bring nearly all the holdings of all libraries and museums within the range of nearly everyone on the globe.”

Common Challenges

Building these large collections of digital content is a massive undertaking and is, of course, not without major challenges. Both HathiTrust and Google Books projects have faced many challenges already, including a number of common issues that we will look at now. Hopefully, the DPLA will be able to take advantage of lessons learned and avoid some of these issues.

Copyright. The Google Books lawsuits are described earlier. To recap, AAP and Google formally resolved their lawsuit in October 2012, but litigation between the Authors Guild and Google continues. A recent victory for Google was the July 2013 ruling that the Authors Guild cannot sue Google as a class-action suit.

HathiTrust has faced legal challenges as well. In September 2011, the Authors Guild filed a federal copyright infringement suit against HathiTrust, the University of Michigan, the University of California, the University of Wisconsin system, Indiana University, and Cornell University for storing digital copies of millions of books. In October 2012, a judge ruled against the Authors Guild in favor of the libraries. HathiTrust has a statement posted on its website regarding the ruling with a quote from Harold Baer, Jr., the presiding judge:

I cannot imagine a definition of fair use that would not encompass the transformative uses made by Defendants’ MDP [Mass Digitization Project] and would require that I terminate this invaluable contribution to the progress of science and cultivation of the arts that at the same time effectuates the ideals espoused by the ADA [Americans With Disabilities Act].

The Authors Guild, however, filed an appeal in November 2012 and, consequently, litigation in The Authors Guild v. HathiTrust case is ongoing as of the time of writing. Meanwhile, academic authors have filed a brief in the case in support of the work of HathiTrust.

Orphan works. Another massive challenge, and one related to copyright, is the issue of orphan works. An orphan work is a copyrighted work for which the copyright owner cannot be contacted. For example, the copyright owner may have died, may be unaware of their ownership, or may even be a company that has gone out of business. In 2011, the University of Michigan Library’s copyright office announced the launch of a new HathiTrust-funded research project to identify in-copyright orphan works in the repository and to begin making some of these titles available to members of the HathiTrust community. The program was halted by the University of Michigan shortly thereafter, however, and is currently undergoing a redesign of the orphan works identification process. At this point, the University of Michigan and HathiTrust have not made any works identified as orphans publicly available, and they have no plans to do so. The DPLA is also struggling with the challenge of orphan works, and the issue of how orphan works were handled by Google was a significant stumbling block in the rejected 2008 Google settlement.

Metadata. Another challenging area with large-scale digital initiatives is metadata. The Google Books project metadata has been described in the past—by Geoff Nunberg in a now infamous 2009 blog post—as a “[m]etadata train wreck” (languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1701). In Google’s defense, however, the extremely large scale of the project means that the error rate will be high. A response in a comment thread from a Google Books manager, Jon Orwant, states that Google has “learned the hard way that when you’re dealing with a trillion metadata fields, one-in-a-million errors happen a million times over.”

The HathiTrust project has, not surprisingly, put great emphasis on providing metadata for its collection. Since its metadata originates from partner libraries, the libraries have the expertise and opportunity—more so than is the case with Google Books—to explore opportunities to enhance existing print cataloguing and to optimize this bibliographic metadata for the digital world. An example of this is the data visualizations for call number, date, and language that are available on the HathiTrust website (hathitrust.org/statistics_info). The DPLA has a two-page metadata policy available on its website that details its “commitment to freely sharable metadata to promote innovation” (dp.la/info/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/DPLAMetadataPolicy.pdf).

Quality. In terms of the quality of large-scale digital libraries and digitization initiatives, the Google Books project in particular has been criticized for concerns over digitization quality, as well as the quality of its metadata. Attention has been drawn to the poor quality of some page scans and to the unreliable and error-laden optical character recognition (OCR), which is the process that makes text machine readable. A 2012 paper published in Literary and Linguistic Computing, written by Paul Gooding (“Mass Digitization and the Garbage Dump: The Conflicting Needs of Quantitative and Qualitative Methods”), attributes the quality issues not only to the scale of these projects but also to the desire to “digitize first and worry about quality later.”

HathiTrust has a statement about its dedication to quality on its website. It is committed to ensuring optimum quality of the content in its repository by applying formal quality review to all content submitted. Discussions around quality and digital repositories underscore the importance of certification for repositories. Digital repository certification is becoming increasingly important as libraries put more of our collections online. TRAC (Trustworthy Repositories Audit and Certification) is a process of audit and certification for digital repositories. The criteria were developed in part by OCLC and the Center for Research Libraries, and version 1.0 was published in 2007. HathiTrust was certified in March 2011. In Canada, the Ontario Council of University Libraries’ Scholars Portal project, a platform that preserves and provides access to the information resources collected and shared by Ontario’s 21 university libraries, is now the first certified trustworthy digital repository in Canada as of early 2013.

Conclusion

This article has looked at three large-scale digitization initiatives: Google Books, HathiTrust, and the DPLA. They are all unique projects with unique goals that, at the same time, struggle with common challenges. Certainly, there is an enormous amount of value in having massive collections of digital books at our fingertips, despite the aforementioned challenges. The year 2013 provides a useful vantage point for looking into these projects, especially since they range in age from nascent to nearly 1 decade. Big developments over the past 12 months have included the launch of the DPLA, a partnership between HathiTrust and the DPLA, a settlement between publishers and Google Books, and the release of a documentary about the Google Books project. Robert Darnton writes that “the DPLA took inspiration from Google’s bold attempt to digitize entire libraries, and [DPLA] still hopes to win Google over as an ally in working for the public good.” There are undoubtedly further developments just around the corner.

|