FEATURE

Revitalizing Library Services With Usability Data: Testing 1, 2, 3 ...

by Emily Mitchell, Brandon West, and Kathryn Johns-Masten

Penfield didn’t have

an existing culture of

usability testing.

That was about to change. |

The library website is vital to patrons’ user experience, whether those patrons are at home, on the road, or in the library. It is also a key component of many librarian and library staff jobs. Despite this fact, gathering usability data about the website usually seems to be the exclusive province of the library’s web developers. In many cases, this means that usability studies are difficult or impossible to sustain and become one-off projects. At the State University of New York–Oswego’s (SUNY–Oswego) Penfield Library, we started off with a single librarian doing usability testing on the website—a model that would have been difficult to sustain—and ended up creating a culture of usability testing that includes most of the librarians on staff and extends beyond the website.

Getting Started

When Penfield’s new webmaster came on board in 2013, she knew that redesigning the library’s homepage was a priority, but she wanted to avoid having advisory web team meetings that devolved into painful political wrangling over differing opinions of what a library website should look like. Usability testing could address her concerns. The data from usability tests would lead to informed decisions about the homepage that could stand up against any librarian’s personal opinion. Unfortunately, Penfield didn’t have an existing culture of usability testing. That was about to change.

After reading a great deal of professional literature and spending time on web resources such as Usability.gov (usability.gov), the webmaster developed a set of questions and the tests and tools needed to answer them (see the sidebar below).

Heat mapping click data revealed, in a highly graphical way, what did and didn’t get used on our homepage during the spring semester. We were able to remove content from the homepage with no argument, as a result of our heat-map image showing actual use patterns.

Card sorting by students allowed us to understand how they thought the website should be organized, or at least how various parts should be interconnected. We mapped the strongest connections between pieces of content to reveal patterns. If two concepts are connected by a line in the resulting diagram (see the sidebar below), at least five of 11 students grouped those items together.

Finally, we observed student behavior while using the site. In completing a specific task, what did they click on first? We also listened to them as they explained, out loud, the steps they were taking to complete a task on the website.

Beyond the Website

What no one in the library had anticipated was the extent to which the homepage usability findings were going to have relevance beyond the website design. Our surveys and card-sort results were packed full of information that—in addition to shaping what the new homepage should look like—would be useful to reference and instruction librarians in general. In fact, many students mentioned that because of their formal library instruction or their experience in asking questions at the reference desk, they found the library website easier to use. Everything was connected to everything else.

After moving on to first-click testing and think-aloud testing, the webmaster quickly realized that although she was trying to evaluate the library homepage, the tests were also evaluating the library’s new discovery service interface (EBSCO Discovery Service; EDS). It was impossible to separate the two during think-aloud usability tests, especially since many students chose to search the library’s discovery tool when looking for citation information or specific databases. Short of taking the search box off the homepage, there seemed to be no way to isolate the usability of the discovery service from the usability of the website. However, it would be possible to incorporate the discovery service into our usability considerations by involving the person responsible for it: the electronic resources librarian.

The webmaster had been sharing what she was learning about the website and how students were accessing library resources with anyone who would listen. Luckily enough, the electronic resources librarian expressed interest and started attending the think-aloud usability tests. Her observations from those tests led to the addition of widgets in EDS, so that we could provide meaningful results to students who came to the site searching for citation-related words and database names, etc.

The electronic resources librarian was not the only one interested in how students made use of the new discovery tool. Instruction librarians wanted to understand how students would interact with it and were eager to learn which features of EDS they would need to highlight in their instructional materials and programs. Usability testing could give them the insight they needed.

Culture of Usability Culture of Usability

The instruction librarians’ interest was an opportunity to begin fostering a culture of usability in the library. The instructional design librarian offered to collaborate with the webmaster and the electronic resources librarian on a round of usability testing focused on the pedagogical aspects of EDS. Since most users start searching EDS from the library homepage and since the electronic resources librarian was still curious whether our current setup was working for students, these usability tests overlapped with many other librarians’ realms of interest. Collaborating to get the data we all needed just made sense.

To spread our findings even further into the library, we made a point of opening this round of testing to any librarian who wanted to observe and/or ask questions at the end of each session. We used our college’s web-conferencing software, Blackboard Collaborate, to share audio and the user’s screen with librarians in another room. Blackboard Collaborate also let us archive test recordings for librarians who were unable to attend.

At the end of these think-aloud usability tests, we learned enough that all the librarians who attended could make more informed decisions about instruction, the EDS interface, and tweaks to the homepage. We also learned enough about the usability-testing process that future tests would be easier to plan and set up. We did not have to wait long for a repeat performance.

For our next round of tests, the instructional design librarian took the lead, focusing on LibGuides. He was planning our migration to the new LibGuides 2 platform, and a key element missing from Penfield’s LibGuides was input from the students. The librarians did not have any evidence that students understood how to navigate the layout chosen when the guides were first adopted in 2009. In collaboration with the webmaster, the instructional design librarian developed a think-aloud test that would take students through the various components of the libguide, such as accessing databases, finding ways to receive help from librarians, and locating background information on topics.

Developing this round of usability testing proved to be easy, since this was the third test being conducted within a relatively short amount of time. Selecting the six tasks to have the students attempt was the most time-consuming part, given the laundry list of ideas that was generated by the larger group of librarians. For everything else, we could reuse the formula we had already developed for think-aloud testing. Human-subjects’ approval was painless to get by simply revising a previous application, changing only the part of the library’s web presence that was to be tested. Everyone was already familiar with the technical setup of a workstation that could share its screen and the user’s voice with observers in another room. And Steve Krug’s script for think-aloud usability testing from Rocket Surgery Made Easy (available at sensible.com/downloads-rsme.html) had become a familiar companion.

Lessons Learned

We learned a lot during this rapid succession of usability tests and the accompanying expansion of our usability culture. One crucial lesson was to recheck all the technology before each session. When we streamed the usability sessions during the EDS tests (our second set of tests), there were no notable issues. When it came time for our LibGuides test, though, we ran into technical problems that weren’t there a few weeks prior. When Blackboard Collaborate was turned on to begin recording the usability test, the audience of eager librarians (who wanted to watch and discuss the testing) was met with what appeared to be a blank screen. As it turns out, the Flash software in the viewing room was out-of-date, which meant that the usability test viewing was a bust.

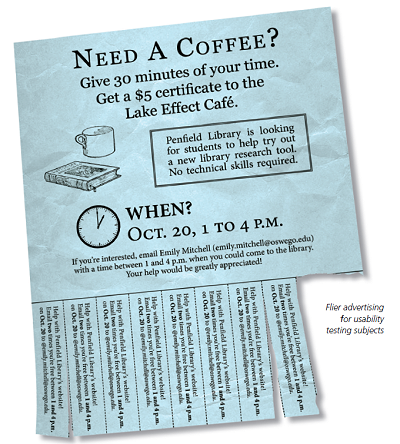

Another important lesson we learned was that some light screening of participants might be necessary to achieve the most meaningful results. After decorating the campus with recruitment signs, we received a handful of test volunteers, whom we later discovered were all computer and information science (CS) majors. This translated into results that reflected strong user knowledge of interface navigation, which likely was not representative of the student population at large. (Most non-CS students probably wouldn’t think to manually manipulate the URL of the page they were on in order to get back to the parent page.) Since all three students were in the same degree program, their feedback didn’t provide us with data that was generalizable to the average computer user. Still, we were able to identify some things that would improve our libguide. As a result, we were able to implement some small changes when we migrated to the new LibGuides platform in December 2014.

Moving Forward

So what now? An important element of all these tests has been making usability a part of Penfield’s culture. We have succeeded to the extent that most of our librarians have a better understanding of what usability testing is and how useful the data it provides can be. Collectively, we realized that usability testing is not all that complicated to pull off, but it can provide many useful insights. We owe a large part of this success to the fact that we opened up the usability sessions for observation to any interested librarian or staff member who wants to sit in.

These observers have not only contributed new ideas to fuel future tests, but they immediately helped maximize results from the current studies, since they were given the opportunity to ask students additional questions after the initial round of usability testing had taken place. Thus, we wound up with more data that’s of more use to a greater number of people. As we continue to talk about usability testing, it becomes that much easier—just another thing that we do naturally.

As we librarians move forward in making more data-informed decisions, it is important for us to make an intentional effort to continue usability testing. We are aiming for at least one usability test a semester, not just limited to website matters. Penfield’s instruction team is developing a new information literacy tutorial, and several librarians have already begun to discuss the importance of conducting usability tests throughout the tutorial development process. In addition, our renovation committee is considering conducting usability testing on specific areas within our building as we start to renovate.

Coming from a group of librarians who had heard little about usability a year ago, this speaks volumes about the value of engaging all librarians in a process that once was the sole purview of a lonely webmaster.

|