FEATURE

Gamification Meets Meaningful Play: An Inside Look

by Jan Zastrow

| It's an exhilarating trend, and one I’d like to see more GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) institutions implement. |

Has your institution gotten on the Pokémon GO bandwagon yet? There’s so much potential to get new users in the door, but it’s so fraught with possibilities for unexpected consequences.

In case you’ve been living under a rock, Pokémon GO is a free, location-based, augmented reality (AR) game developed by Niantic for iOS and Android devices. AR refers to real-life settings with virtual (often 3D) effects overlaid onto real-world surroundings, usually viewed through a camera, appearing as part of the physical environment.

Released in July 2016, Pokémon GO allows players to use the GPS capability of their mobile devices to locate, capture, battle, and train virtual creatures (Pokémon) that appear on the screen as if they were in the same real-world location as the player. While its positives include popularizing AR gaming, promoting physical activity, and supporting local businesses, the game is also controversial for contributing to accidents and becoming a public nuisance at certain cultural heritage locations.1

Arlington Cemetery and the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., have banned the game. “Playing the game is not appropriate in the museum, which is a memorial to the victims of Nazism,” explains Andrew Hollinger, the Holocaust Museum’s communications director. One image circulating online shows a player encountering an unsettling digital critter inside the museum: a Pokémon called Koffing that emits poisonous gas floating by a sign for the museum’s auditorium—which portrays the testimonials of Jews who survived the gas chambers. “We are trying to find out if we can get the museum excluded from the game,” says Hollinger.2

Serious Games, Meaningful Play

But while Pokémon GO may be the biggest, most popular AR craze we’ve ever seen, it’s only one example of an AR game. In a more educational vein, academics in Taiwan are experimenting with AR applications to teach local history and architecture. Dubbed the Digital ARt/ARchitecture Project, the two 3D AR applications—a game called Hukou Old Street 3D AR and the Hsinchu County History Museum AR Tour—provide strong stimulation to engage users in learning about art and culture. But while Pokémon GO may be the biggest, most popular AR craze we’ve ever seen, it’s only one example of an AR game. In a more educational vein, academics in Taiwan are experimenting with AR applications to teach local history and architecture. Dubbed the Digital ARt/ARchitecture Project, the two 3D AR applications—a game called Hukou Old Street 3D AR and the Hsinchu County History Museum AR Tour—provide strong stimulation to engage users in learning about art and culture.

Hukou Old Street and Hsinchu County leverage content from historical archives and architecture to blend real objects and virtual content to create serious teaching games. By using AR imaging techniques, the users are immersed in virtual exhibitions and learn in a “surround-around” ubiquitous computing environment. The Hukou Old Street game “brings the beauty of Hukou local culture and traditional architecture into the palms of players. But the purpose for designing this game is to stimulate players to pay a visit to present-day Hukou Old Street and to taste the cultural atmosphere in person.”3 Just as in Pokémon GO, the impetus is getting players out into the real world.

“This project makes cultural and historical materials portable and interactive, and furthermore, transforms users into players to interact with AR content in an intuitive and exciting manner” (Shih, Lin, and Tseng 2015). It’s an exhilarating trend, and one I’d like to see more GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) institutions implement.

Docugames

Another genre of serious games for learning is the “docugame,” which uses digital archival documents in elearning games based on historical events. One example from Australia is AE2 Commander, a role-play elearning docugame that authentically recreates a historical mission forming part of the unsuccessful Allied campaign on the Gallipoli Peninsula in April 1915. The players use digitized documents of original source records held by the Australian War Memorial and National Archives, providing essential intelligence to get to the next stage of the game.4

“As on-demand and preemptive digitization bring important collections online, opportunities exist to engage new audiences and leverage this activity in ways that are transformative in terms of public perception of important cultural institutions. … Docugames are a new and exciting way of connecting users with important cultural heritage in digital format. Current work has merely scratched the surface of what might be possible with docugames and how they might transform the user experience of cultural heritage online” (Brogan and Masek 2013).

Metadata as a Game

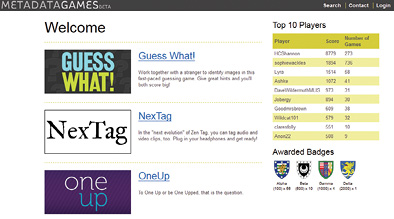

A third genre integrates crowdsourcing with metadata creation in a suite called Metadata Games. This open source game platform uses more than 45 collections at 11 different institutions and includes tens of thousands of media items—images, audio, and video—that have generated 167,000-plus tags so far.5 A third genre integrates crowdsourcing with metadata creation in a suite called Metadata Games. This open source game platform uses more than 45 collections at 11 different institutions and includes tens of thousands of media items—images, audio, and video—that have generated 167,000-plus tags so far.5

Started with grant funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in 2009, Metadata Games set out to remedy the lack of cataloging suffered by most mass-digitization projects by making it fun and interesting for virtual volunteers to provide tags in an entertaining and participatory way. The diverse players provide more metadata than a single staff member could come up with alone and often contribute specialized knowledge that may be otherwise difficult to collect.6

One of the cleverest games is called Guess What!, a real-time collaborative two-player game in which one player sees a single image of, say, a mammal on her screen, and the other player sees a dozen images of mammals on his screen. Player One must describe the picture accurately enough so that Player Two can correctly select the image from the array. “Players enjoy giving each other accurate but arcane hints, thus raising the specificity of the vocabulary terms used. The game serves the goal of the project in two ways: it helps to collect new metadata on images that have none prior, and it helps verify existing terms by monitoring their frequency of use among players” (Flanagan and Carini 2012).

Why do these virtual volunteers do it? In a 2013 interview, Mary Flanagan—a designer, writer, and artist for Metadata Games and a professor of digital humanities at Dartmouth College—gave details: “We have three motivations in terms of audience/players, with overlaps among them. One motivation is to assist a particular institution, or simply contribute to a good cause. These players first and foremost like the idea of helping. A second motivation for players is to play because they love a subject area—they like tagging buildings, or playing games about parts of boats, or dog breeds for example. A third player motivation is simply to win—to be the best, the fastest and most accurate.” 7

That last element is satisfied by the Arcade,8 the splash page of the game site in which players’ scores can be displayed across the suite of games that a participating institution hosts. This offers the competitive “juice” some players need for a game to be fun. That last element is satisfied by the Arcade,8 the splash page of the game site in which players’ scores can be displayed across the suite of games that a participating institution hosts. This offers the competitive “juice” some players need for a game to be fun.

The Metadata Games project is still going strong. A 2015 study9 found the value of patron-generated “folksonomies” enhanced findability and confirmed the ability of the general public to contribute meaningful metadata. This could prove to be a game changer (pun intended) for the way GLAM institutions organize materials and handle classification in the future.

What’s next? The tagging of audio and video content. Try the addictive Metadata Game NexTag, in which you watch four historical video/audio clips and tag them with keywords and phrases. Betcha can’t stop at just one!

|