FEATURE

Connection, Not Collection: Using iBeacons to Engage Library Users

by Sidney Eng

| Libraries and museums are using beacons to alert patrons with notices about services and exhibits when they are in physical proximity of the devices. |

The library exists for its users, just as books exist for their readers. But the expectation of library services has changed. One does not have to look further than the annual “NMC Horizon Report” to demonstrate that pressure continues to mount for the library to realign itself to fit a new user environment.

It is not simply that librarians need to prove our value to the public or the administration—which, admittedly, is essential for funding and support—we also want to facilitate the relationship between resources and patrons. It is no longer just a question of access to content, but connecting to users in ways familiar to them. We must go where the patrons are. Our iBeacon project, begun in 2015, reaches out to them on their devices.

What’s an iBeacon?

iBeacons—or, generically speaking, “beacons”—are a Bluetooth noti fication technology used to transmit targeted messages to smartphones and other devices. Libraries and museums are using beacons to alert patrons with notices about services and exhibits when they are in physical proximity of the devices.

Students opt in by downloading an app to receive the beacon’s Bluetooth signal. But they do not need to activate the app to receive the messages. As long as a person is in the proximity of the physical beacon (transmittal ranges vary and are generally less than 200'), they can receive notifications.

CapiraConnect is one of the two companies (Enis 2014) with several mobile products developed specifically for libraries. The other is BluuBeam. The custom-written apps are used to promote services and resources. We see the potential to expand notifications to include such library messaging as renewal and overdue notices.

How iBeacon Technology Works

The transmitters—commonly known as iBeacons—are little computers that use Bluetooth low energy (BLE) technology. “iBeacon” is an Apple product, but it is also an open standard that is used by different providers and can run on the Android platform. Therefore, it may be more appropriate to use the word “beacon” generically. The beacons are manufactured by various companies (Aislelabs 2015). The brand that was supplied to us is Estimote. Almost all beacons run on batteries. Because of their low energy consumption, they can run for a long time without maintenance. The small iBeacons derive their computing capability—such as processing actions or keeping statistics—from the servers (in the cloud) via an app interface. Most technical issues come from writing the code, managing the cloud, or gaining access to services APIs. It is the vendor’s responsibility to maintain these functions.

All the beacons within an area continually emit low energy signals. When in proximity, a student’s smartphone receives and responds to the beacons. The location of the person is identified, and targeted messages or service are triggered. The location is calculated based on the distance between the device (e.g., an iPhone) and the beacons. Think of the beacons as the lighthouses for ships in maritime navigation. The strength and the frequency of the radio signals picked up by the device will give an estimation of the location of the library patron. The farther someone is from the transmitter, the weaker the signal. The default standard is set for the signals to be transmitted five times a second. The smartphone does not have to be turned on to be pinged and monitored. Multiple beacons constitute zones, with a device entering, exiting, or re-entering a zone. The pattern of traffic can be studied.

The simplest application is to send messages about events or services based on location. The app works in the background. Imagine receiving a message that a book you have placed a hold on has arrived as you are browsing in the stacks!

|

The Backstory

Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) is an urban commuter school. As my City University of New York (CUNY) colleagues suggest, our students are mobile by default. Not only is there a high rate of smartphone use, we have found that students use their commuting time on mass transit to do academic work via their devices and to access library services and content.

BMCC’s library is not new to mobile apps, although our previous experiment in 2009 did not take off. In hindsight, we did not promote the idea properly. The installation required an active and continued effort from the students, and with the subsequent creation of a responsive website, the old app became obsolete.

In 2013, the BMCC library conducted a survey of student awareness of library services. The findings pointed to an alarming lack of awareness. Some of the students did not even know that they could borrow books from the library or make photocopies. Less than 20% knew we loaned calculators and e-readers, and less than 40% were aware of our email and chat reference services. All were cause for deep concern.

When the college dedicated a new building and designated three floors connected by internal staircases as “library study space”—presently outfit ted with iPads but no librarians—the calculus of our thinking changed.

How could we engage students and connect to faculty members in such an area? A location-aware service such as iBeacon could define a learning relationship in places where the librarians ought to have a presence but cannot. The inexpensive Bluetooth low engery (BLE) sensors might eventually give us a platform to combine hardware, software, and service innovation in the new space, but we needed to test them first. We are using our main library as the test bed.

Locations and Placement of Our Beacons

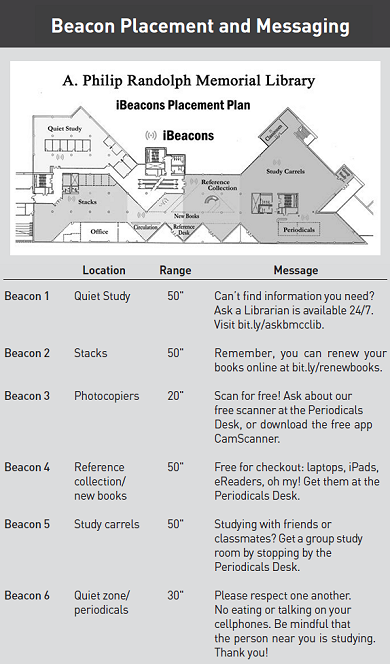

Our library has a relatively small footprint. We placed six beacons throughout the library and developed targeted messages appropriate to each particular location (stacks, quiet study area, and new book displays, etc.).

There has been some discussion about the angles and heights above the floor at which the beacons should be mounted. We did not see much difference in our early experiments. The signals are strongest when the signal range is set to a shorter distance. In such a case, a student would have to be close to the sensors to receive an alert. If the range is set too high, the alerts become less accurate or conflicting, and the library did not want the patrons to be annoyed or confused by several messages. So we decided to set the range on the short side.

The beacons are inexpensive but not unattractive. To avoid being physically removed by curious individuals, they should be kept high out of reach or hidden. If you have recessed ceilings, it is ideal to put them on the grids just as you might mount Wi-Fi antennas. If they are visible, pick the color or shape compatible with your library decor. There was a report about holding them by a tilted bracket for better signals, but it made no difference in our pilot. Place them wherever it fits with your interior.

Varying the distances between sensors is necessary to avoid the possibility of sending overlapping messages. The different distances are a way to create zones; as students enter a zone, ideally, they will receive just one message. Placing the beacons is relatively simple. The more challenging task is selecting appropriate messages for your notification system.

Targeted Messages Used in BMCC’s Configuration

We located our beacons as indicated in the image to the right. You can also see the message each beacon sends.

We spent a considerable amount of time thinking of these simple messages, with the initial samples largely suggested by the outreach librarian.

In the area near the group study rooms, we advertise our 24/7 chat reference service (QuestionPoint). In the large span of study carrels, we promote the use of group study rooms. This will change to a message promoting one-on-one research consultation near exam times.

As a rule of thumb, the messages should be personal, relevant, and interesting so the students relate to them. Ideally, the messages will call for some sort of action by the recipients. When we send invitations to form a student focus group, it will be a test of the effectiveness of the beacon system. How fast and how large will the response be?

Other Considerations

Some different issues to address when deploying a technology such as this are data security, privacy, and the potential for hacking or spoofing.

When I raised the issue of spoofing the vendor’s reply was that the data are in the cloud and not to worry. That is a misstatement. Services provided in the cloud are subject to the same kind of common threats and hacking that require being vigilant with our own library systems. Luckily, the notification function—which is technically susceptible to hijacking—will be an unlikely target for hackers. While we may worry about our messages being replaced by pranks, there is little incentive to do so. Another issue is privacy and data security. As a notification system, the app does not collect personal data. When library processing is involved, the operation is done elsewhere and subject to the other systems’ safeguards. It is important to be sure that password-based authentications are encrypted. If business intelligence or profiling is contemplated in a more advanced operation, anonymity should be maintained 100%, and privacy reminders should be broadcast regularly. After all, this is a consumer education function (Spina 2015).

Project Assessment and Statistics

Every pilot project should include an assessment plan. How else would you know if it is effective and services have been improved? These are some of the indicators we will look for when we conduct our final evaluation:

- The number of app downloads and apps deleted (faculty users and student users may differ in their responses)

- The number of responses to the calls for action delivered to user devices

- A comparison of service activity levels before and after the project was launched

- Feedback from users, collected through a survey distributed by the beacons

- New book circulation statistics

As noted previously, it might be ideal to put beacons in our new librarianless building to interact with students from that site, but we will not know until the results are in from our pilot later this year.

Making Innovation a Priority

Successful libraries look for opportunities to add value for their users by responding to how the patrons find and use information. The beacon system represents a new way for the library to provide and market its resources and services in a way that is consistent with the communications methods being employed by today’s device-enabled users.

For library managers, the challenge is not only what innovations to implement, but also when to adopt new technology. Does being an early adopter carry more risks or extra dividends? Quick deployment was our strategy, because we felt denial of such a useful service was contrary to the library’s mission. In the early adoption of a technology, failure is only an option if we document and learn from the experience. We’ll soon find out whether the students will include the library as part of their everyday lifestyle. Until then, we are innovating as we go.

|