|

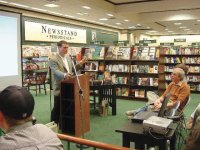

Taking a picture from the back of the room shows

only the speaker’s face, not the listeners’ faces.

[Click for full-size image] |

|

The attendee in the front row is a library staffer who

gave his permission to be photographed.

[Click for full-size image] |

| Photos courtesy of Western Kentucky University Libraries |

|

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a substantial increase in the number of programs that libraries sponsor. It seems natural to document events by taking photographs. Pictures can be a powerful way of justifying a programming budget and can also be useful in attracting people to future lectures and programs. However, there are a few legal issues relating to photography that librarians need to be aware of, particularly the rights of privacy and publicity. In some situations, using a photograph of an identifiable person could be a one-way ticket to a lawsuit.

There are many uses of photographs that require signed consent forms. Whether you need permission to utilize photographs you take at library events depends on how they will be used and if the people in the pictures can be identified. If the picture contains identifiable people, you must always ask permission before using it for marketing or promotion. On the other hand, photographs in which the subjects are not identifiable (for example, a crowd shot taken from behind with no faces visible) do not require permission. In addition, pictures that accompany current news stories do not need consent forms.

Rights of Publicity and Privacy

The right of publicity is actually an outgrowth of the right of privacy—first formulated by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in a famous 1890 Harvard Law Review article1—as well as the statutory and common law of trademarks.2 Many states have also passed privacy and publicity statutes.3 The first statute was enacted in New York in 1903; it is still in effect.4 Although most publicity cases involve celebrities, the law applies to everyone equally, including people in photographs taken at library programs.

State laws differ about the scope of publicity. However, the general rule is this: “The Right of Publicity provides to each and every person the right to use his or her persona for his or her benefit and provides a cause of action to stop the unauthorized use of that persona for commercial purposes.”5 The “persona” includes the person’s name, image, or voice or any recognizable attribute.6

It is possible to use a persona even when the subject in the image is not identifiable. The Professional Photographer’s Legal Handbook7 uses a photo of astronaut Buzz Aldrin as an example. All the picture shows is an astronaut in a spacesuit standing on the moon, with another astronaut reflected in his visor. However, the photograph is so famous that a viewer would be able to identify the astronaut.8

It is clearly a violation of the right of publicity to use photographs from library programs in order to market or advertise the library or to call attention to future programming. You should always get written consent if you plan to use images for these purposes. If the subject is under 18, the parent or guardian should sign a consent form.

One way to get around this problem is to take photos that don’t include identifiable people. For example, you could take a picture of the crowd from the back of the room. That way, you won’t have to worry about being able to see faces.

The law is a bit more lenient toward pictures that are published in a newspaper or library newsletter. Because the First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press, news media may publish names, likenesses, and images as long as they are part of a “newsworthy context.”9 (Even news media are forbidden from using photos or other images for commercial purposes.)

A library’s newsletter qualifies as news media. Online blogs and “recent events” websites are also considered to be “news.” However, the photographs should only be posted for a limited amount of time. (One source suggests no longer than 2 weeks.10) Flickr, Facebook, MySpace, and other social networking sites create new issues. The problem is the limited amount of time that “news” images can be posted online without requesting permission from the subject. The right of publicity applies equally to blogs, websites, and social networking sites. So I do not recommend using Flickr or other such sites to archive photographs. It is important to be sure that you are really doing a “news” story on the event that just occurred rather than promoting future programs. This doesn’t mean you can’t mention upcoming programs in the article. However, the focus of the article should be the event that just concluded, rather than upcoming ones.

What Should Be in a Consent Form

The University of Arizona Web Developers Group has created an excellent webpage on the topic of photographs and releases.11 In addition to useful information, the website contains a model release form. This model form provides a good starting point. However, as with anything else, it is always a good idea to run a form past your institutional attorney in order to assure that it addresses the laws of your state. (In fact—I can’t stress this point enough—whenever you have questions about the legality of a form, always ask your institutional attorney. It saves so much grief down the road.)

Although language may vary in different states, all consent forms do have a few necessary elements:

-

Who has permission to use the pictures? Generally, this is the library and its agents or employees.

-

For which pictures has consent been given? The easiest way to do this is to have a blank line at the bottom of the form where the date and location can be filled in. The Arizona model consent form grants permission “to use photographs taken of me on the date and at the location listed below....”12

-

For what purpose will the pictures be used? Will they be used for advertising purposes, in library newsletters, or on the website? It is usually better to get permission for a broad range of activities, since you may wish to use a photo for a different purpose in the future.

-

Waiver of notification or inspection before publication. Include a clause in the consent form specifying that you don’t have to get any further permission or provide any notification before using the pictures. You should also have language stating that the subject does not have the right to inspect or approve pictures before they can be used. The Arizona model form contains this language.

-

Release of rights. This part is tricky because the necessary legal language varies among states. However, there should be a clause in the consent form specifying that the subject will not sue you for utilizing the picture. The Arizona model form uses the following language: “I hereby agree to release, defend, and hold harmless the Arizona Board of Regents, on behalf of The University of Arizona and its agents or employees, including any firm publishing and/or distributing the finished product in whole or in part, from and against any claims, damages or liability arising from or related to the use of the photographs, including but not limited to any misuse, distortion, blurring, alteration, optical illusion, or in the taking, processing, reduction or production of the finished product, its publication or distribution.”

-

An affirmation that the subject (or parent or guardian) is over the age of 18 and understands what he or she is signing. The Arizona model form also specifies that the signer is “competent to contract....” (If you do library programs in a psychiatric hospital, have the guardian sign your consent form.)

-

A signature and date of signing. The easiest way to handle the affirmation and signature is to have one line for subjects over 18 to sign and a separate line for parents or guardians. You should also include a place to enter the date when the form was signed.

As I mentioned above, you should ensure that the consent form uses the proper language for your state. Having a consent form with invalid language is as bad as having no consent form. The two clauses that are most likely to vary are the release of rights and the affirmation, so check the language with your attorney.

Keeping Your Consent Forms

How long should you retain these signed consent forms? This is really more of a records-management question than anything else. Although most libraries don’t have their own records managers, the larger institution usually does.

Record-retention questions get a bit tricky when dealing with nonprofit organizations, particularly ones that receive a substantial amount of their budgets from public funds. Again, libraries that are part of a larger entity should consult their parent organization. However, that doesn’t help small nonprofits that are stand-alone entities.

In many states, private entities that receive more than 25% of their funding from governmental bodies are bound by statutes such as open records and open meetings acts. Sometimes this includes record-retention policies as well. If your library does not have a record-retention policy and is not part of a larger entity, I would suggest consulting with the governmental unit that the funding comes from. The municipal or county attorney or the records manager may be able to help you determine whether you are bound by governmental record-retention laws. The state attorney general’s office is another place to look for guidance.

Another way to think about consent forms is to keep them for as long as it is possible to get sued. The amount of time that a lawsuit can be brought (known as the “statute of limitations”) varies from state to state. Because the right of publicity is an offshoot of the right of privacy, many states base the statute of limitations for publicity actions on the allowable time period for bringing privacy claims. According to the legal encyclopedia American Jurisprudence, the longest time period is 6 years in New Jersey.13 So I would recommend keeping your consent forms at least that long.

Follow the Letter of the Law

If you plan to utilize images with identifiable people for public relations, marketing, or promotional purposes, always use a written consent form. (Oral consent is worth the paper it is written on.) If the subject is under the age of 18, be sure to get a signature from a parent or guardian. You don’t need permission to run a story about a recent event in your newsletter or on your blog. However, the story really has to be about the program, not just a promotion for the next event. And check with your institutional attorney or records manager to find out how long you need to retain the signed forms.

Librarians who follow these principles and receive advice from records managers and attorneys should be safe from lawsuits. That’s the goal of your attorney and of this article.

|